Jews at the Gates of Law

FROM THE EDITOR

“Before the Law,” one of Franz Kafka’s best-known short stories, opens with a conversation between a gatekeeper and a country man:

Before the law sits a gatekeeper. To this gatekeeper comes a man from the country who asks to be permitted entry into the law. But the gatekeeper says that he cannot grant him entry at the moment. The man thinks about it and then asks if he will be allowed to come in later. “It is possible,” says the gatekeeper, “but not now.”

The country man peeks through the gate, only to be warned that should he manage to overcome the gatekeeper and cross the threshold, he will find other gates with stronger gatekeepers ahead of him. And so, the country man sits on a stool, waiting, for years. As he nears death, he asks the gatekeeper one last question:

“Everyone strives after the law,” says the man, “so how is it that in these many years no one but me has requested entry?” The gatekeeper sees that the man is already dying and, in order to reach his diminishing sense of hearing, he shouts at him, “Here no one else can gain entry, since this entrance was assigned only to you. I’m going now to close it.”

And as the gate closes and the man dies, the story ends, just a few short paragraphs after it began.

If you’ve ever stood in line at a government office, only to be told when you reach the front that you’ll need to go to another room and wait in another line there before you can complete whatever task you’ve set out to do, this story likely resonates as a parable of modern bureaucracy. I was reminded of it a few weeks ago, as I sat waiting to be called up to verify my eye color, height, and weight with a clerk at my local Department of Motor Vehicles, having already waited in line once to verify my identity and a second time to pose for a photograph.

But law regulates much more than the who, what, when, where and how of driving, and what I love about this story is how it stretches to shed light on law from many different angles. We might understand Kafka’s system of gates and gatekeepers as a state judicial system—not as a bureaucracy (though it certainly has that element), but as a system of legal interpretation and application. Reading the story in this way, I wonder, what if the country man had pushed back, if he had said, “No! This is my law, and I demand that the law see me as I am and open itself to my experience. I have come all the way from the country, and I demand to be recognized”? Kafka—whose experience of life was permeated by the layers of alienation that appear metaphorically in his stories and novels—did not write the story this way, and it’s hard to imagine that he could have. But I would argue that in a democracy, where the law’s authority ultimately rests with the people, the law must recognize and respond to those who stand before it.

Love Jewish Ideas?

Subscribe to the print edition of Sources today.

I also think we can read this story as a parable about halakhah, Jewish law. (Kafka wrestled with his Jewishness throughout his life, and “Before the Law” was first published in 1915 in Selbstwehr, a Jewish publication.) Halakhah’s authority derives from the divine revelation found in the Torah. In day-to-day life, it is interpreted—at least on a formal level—by rabbis and other scholars, while the divine Lawmaker remains inaccessible. We might liken the country man to the Jew seeking to understand what God expects of her; halakhah is simultaneously a way toward that understanding and an endless maze made up of layers upon layers of interpretation that can obscure rather than reveal the presence of God.

We might hope that the rabbis and scholars who stand as gatekeepers will open the gates of halakhah, but sometimes the gates to deeper understanding remain stubbornly closed. Some of us leave the divine behind completely; some of us seek other gates to God; some of us sit and wait quietly; some of us persistently examine the gate until we can see for ourselves how to get in. Some of us choose to train as gatekeepers ourselves. This array of options also sets halakhah apart from other legal systems. While the social pressure to keep a kosher home and observe Shabbat serves as an enforcing mechanism in some communities, living one’s life according to halakhah is effectively voluntary. Most any survey will tell you that the number of Jewish communities in which halakhah is at least partially disregarded is far larger than those in which it sets all the behavioral norms.

I am thinking about “Before the Law” because the Spring 2023 issue of Sources is anchored by several essays on law in contemporary Jewish life. The first two pieces explore halakhah in light of the concept of mitzvah, usually translated as “commandment,” in liberal Judaism. Rabbi Elliot Cosgrove argues that the fulfillment of individually selected mitzvot has come to replace the role once played by halakhah in defining Jewishness. Understood in this way, mitzvah now designates a voluntary activity that an individual Jew may take on as an expression of Jewish identity or for personal spiritual fulfillment, and the idea of halakhah as a binding system of law is no longer compelling. Cosgrove ends by calling for the modern movements of Judaism to respond by adjusting their teachings and ideologies to match this reality.

Rabbi Leon Morris also writes about mitzvot having taken the place of halakhah, but he is more hesitant about our embrace of choice as a prized value. It is possible, he argues, to have too much autonomy, and liberal Jews should renew the idea of commandedness, that is, the state of acting Jewishly not out of choice, but out of a sense of obligation that underlies the original idea of a mitzvah. This, he argues, will make Jewish practice more meaningful and more compelling.

The next pieces look at Jewish life vis-à-vis state law, particularly in the United States and Israel. In an essay on the American Supreme Court’s 2022 ruling against a federal right to abortion in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health, Isaac Weiner explores how the Court understands religion and religious freedom, and what these might mean for American Jews and Judaism. Israel—with its dual identity as a Jewish and a democratic state—must wrestle with religion in a different way; in her essay on gender equality, Yofi Tirosh raises doubts about the High Court of Justice’s history of minimizing the appearance of conflict between state law and halakhah.

In the final pieces of this section, authors Micha’el Rosenberg and Meirav Jones each assume and then critique the more traditional view of halakhah as a system of law rooted in obligation. Rosenberg writes theologically, reflecting on what we might mean when we talk—or don’t talk—about God as the source of halakhah. Jones, in contrast, is wary of the way halakhah can limit ritual creativity and flexibility, a phenomenon she illustrates with both the historical example of a so-called mikveh rebellion in 1176 Egypt and the contemporary example of halakhic infertility.

The second half of the journal moves beyond the anchor theme of Jews and Law. The Prescription section of each issue of Sources is designed to identify challenges in contemporary Jewish life and to suggest potential solutions. Both Prescription pieces here focus on Israel. First, Leah Solomon reflects on the meaning of current threats to Israeli democracy for Jews and Palestinians. Second, Dyonna Ginsburg’s piece takes a wider lens, looking historically at the role Israel has played in the world, and then calling for the state to return to a more active role in supporting other nations.

The Close Reading section of Sources features new readings of familiar Jewish texts. Here, Rabbi Joshua Cahan offers a new take on the Passover Haggadah, and more specifically, on the purpose of retelling the story of the exodus at the Seder each year. Finally, the journal closes with a new section, From the Archives, which features historical writing. In this issue, Zev Eleff takes us to a summer night in 1877 at New York’s Grand Union Hotel, when a clerk refused to rent a room to a Jewish guest, even though the guest, Joseph Seligman, had stayed there many times before. Eleff investigates further and draws some interesting lessons for our own concerns about antisemitism in America.

Contemporary events in the United States and Israel make us more aware than ever of the role that law plays in shaping what it means to be human and what it means to be Jewish, and the articles in this issue push us toward a deeper understanding of these realities. In addition, I hope that you will be struck, as I was, by the many other concepts that resonate and reverberate among the articles. Some of these—Zionism and antisemitism, for example—are also of particular interest at this moment. Others are more evergreen. I hope that you will come away from this issue as I have, with new perspectives on each one and how they are interwoven. Though I love Kafka’s story, I don’t share his pessimism; I believe it is possible to get closer to or even to enter the gates of law, and with careful thought and analysis, to understand them better.

Claire E. Sufrin

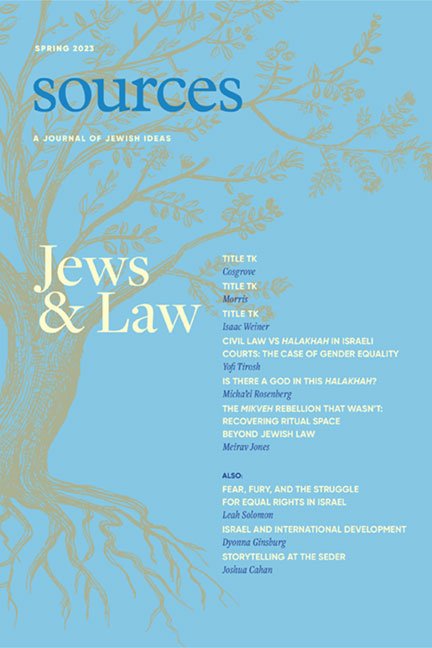

This article appears in Sources, Spring 2023.