Storytelling at the Seder: <em>Lesaper, Lehaggid,</em> and the Purpose of the Haggadah

CLOSE READJoshua Cahan

Joshua Cahan compiled and edited the Yedid Nefesh Bencher and the Yedid Nefesh Haggadah.

Even if we were all sages, all wise, all learned in Torah, we would be obligated to tell the story of the Exodus. And anyone who tells the story of the Exodus in greater depth is to be praised. Once [5 Sages] sat together in Bnei Brak and went on telling the story of the Exodus from Egypt the entire night…

Retelling the grand drama of our departure from Egypt, discussing it, and probing it, and looking for new ways to relate to it: almost every commentator writing about the Seder begins by emphasizing that the central obligation of this night is to tell the story, ideally at great length. Whether through acting or analysis or making connections to our own experience, we look for ways to immerse ourselves in this story. These lines from the beginning of the Maggid section define the Seder and drive home the point: there is no such thing as too much story. It is sometimes even a point of pride to announce how late into the night one’s Seder lasted.

But the Haggadah, the Seder’s ritual script, is strikingly ill-matched to the task of retelling. The Maggid, the storytelling portion of the Haggadah, is lengthy, yet it seems to dispense with the story of the exodus in the barest of details and go on to other things. Where is Moses, or any of the other major characters? Where are the moments of high drama? If telling the story of the exodus is our essential task at the Seder, it might seem that the Haggadah is more of an impediment than a facilitator.

It might help to remember that the Haggadah is, like many liturgical texts, a composite that cannot be expected to flow in a simple, linear fashion. But I will argue that the main problem is that we are actually misunderstanding what it means to “tell the story” of the exodus. We see this when we step back to think historically.

The Haggadah first developed around a guiding principle very different from our contemporary expectations, one that closely reflects earlier biblical and rabbinic sources. In short, the original task of the Seder was not to tell our story but to tell God’s story; it was not to talk about how we were slaves but rather to appreciate and celebrate the fact that, by the grace of God, we are not and will not be slaves.

In the conceptual world of the Torah, this version of the story is not only the focus of the Seder but also the linchpin of Jewish tradition; our entire commitment to serving God is an expression of our gratitude for God’s salvation. The critical task of the Seder is to make that salvation personal by conveying to our children that not only our ancestors but we ourselves, in the present, owe our freedom and our very identity as a People to God’s kindness. As long as we are busy looking for a story that was never meant to be there, we risk overlooking this key theme at the heart of the Haggadah.

From Haggadah to Sipur

Rabbis throughout the medieval and modern periods consistently present the central mitzvah of the Seder as lesaper, to retell or to recount the story of the exodus. The term suggests a detailed narrative, a sense reinforced by the idea that the more we draw out or elaborate on the story the better. Maimonides, in the 12th century, for example, begins his discussion thus:

It is a positive commandment of the Torah to recount [lesaper] the miracles and wonders wrought for our ancestors in Egypt on the night of the fifteenth of Nisan.…Whoever recounts at greater length [marbeh lesaper] the events which took place is worthy of praise. (Hilkhot hametz umatzah, Laws of Hametz & Matzah 7:1)

Indeed, recounting the story of the exodus is the only element other than eating matzah that Maimonides designates as essential.

Love Jewish Ideas?

Subscribe to the print edition of Sources today.

The chasm between our expectations for Seder storytelling and what our text has to offer opens up as soon as the Maggid begins. Right when we are settling in for a story to answer the four questions, the Haggadah offers these two sentences:

We were slaves [avadim hayinu] to Pharaoh in Egypt, but Adonai our God brought us out from there with a mighty hand and an outstretched arm. And had the Holy One not brought our ancestors out from Egypt, we, our children, and our children's children would still be slaves to Pharaoh in Egypt.

This very, very short version of the exodus story, a rephrasing of Deuteronomy 6:21, notes the Israelite enslavement but emphasizes God’s actions, in line with the commandment of lehaggid to one’s children that we noted above. In short, it instructs us—and our children, in particular—to celebrate Passover because God saved us from slavery.

Let’s put this in the context of the Mishnah’s guidelines for teaching children about the exodus at the Seder. The four questions we find in the Haggadah draw from Mishnah Pesachim 10:4, which provides detailed questions that the child may (or perhaps must) ask about the Seder ritual. But for the parent’s response, the Mishnah provides only the following guidelines:

According to the son's knowledge, his father teaches him.

He begins with genut [disgrace] and concludes with shevach [glory/praise].

And he interprets [doresh] the passage: “My father was a wandering Aramean," until he concludes the entire section.

The first line tells us that the response should be variable, tailored to the understanding of the particular child. The second sets the story’s basic framework: it should have a starting point, an end point, and a narrative arc, leaving the rest to be filled in. The third line of the Mishnah identifies a passage from Deuteronomy 26 that briefly recapitulates the events of the exodus and instructs us to interpret or study it closely in the manner of rabbinic midrash. Each of these is indeed a key part of the Maggid: the tradition of the four children expands on the idea of teaching each child according to her needs; two different proposals for texts that go from genut to shevach are included, avadim hayinu and a text from Joshua 24; and the longest section of the Maggid is a phrase-by-phrase interpretation of the passage, “My father was a wandering Aramean.”

Avadim Hayinu is intended to fulfill the second guideline. The words at the center of that guideline, genut and shevach, suggest that the story we tell should trace the Israelites’ journey from disgrace to glory, from oppression to triumph. In Exodus 1-12, which traces the experience of Moses and the Israelites suffering from and then breaking free of Egyptian oppression, is indeed such a story.

But by this measure, the avadim hayinu passage in the Haggadah falls woefully short. It has the proper beginning and end, but that’s it. There is no middle and no elaboration to fill in what is missing. This has long been a major source of confusion for commentators. They posit that it is only intended as an opening, that it only indicates the starting point of the story rather than the whole story, or that it is a summary or abstract that precedes a fuller retelling. But these proposals merely highlight the simple fact that this is not the story we were led to expect. And none are at all convincing since these two sentences clearly read as a self-contained unit, not as an introduction to something more expansive.

Let’s take a step back and return to the Mishnah and, more specifically, its directive that parents teach their children a story that moves from genut to shevach. Although the word shevach can mean “glory,” and at first glance seems to mean just that in the Mishnah, it is more typically used to signify “praise,” specifically praise of God. Understanding shevach as praise of God changes our understanding of the story the Mishnah wants us to tell. Rather than a story of Israel’s transformation from degradation to glory, we are to tell a narrative that begins with Israel’s degradation and concludes with a celebration of God’s might and love, as evidenced by the miracles of the exodus. Looking back at avadim hayinu with this expectation, we can see that, indeed, it begins with the Israelites’ slavery and ends by describing the wonders God performed in the course of leading them to freedom. But we can go further, because these two elements are in fact the whole story. Perhaps, then, the directive is not “go from disgrace to glory” but only “mention disgrace and glory.”

In fact, the four times the Torah commands us to tell our children of the exodus (Ex. 12:27, Ex. 13:8 and 14, Deut. 6:21), it follows a similarly simple paradigm: (1) we were oppressed, but (2) we are no longer oppressed, thanks to God’s mighty and wondrous deeds. Degradation and praise are the only necessary points. Unlike later traditions, the goal of this telling is to instill in the children a sense of gratitude to God that will move them to join in the ritual and celebration, for which these two points suffice.

This affirms our sense that avadim hayinu was proposed as a complete fulfillment of the Mishnah’s mandate to tell a story that ends in praise of God. The Haggadah makes this clear in the next sentence, when it goes on to specify the moral of the avadim hayinu story: “Had the Holy One not brought our ancestors out from Egypt, we, our children, and our children’s children would still be slaves to Pharaoh in Egypt.” This claim is implausible, living as we do, generations and centuries later, but it highlights the true purpose of lehaggid. It suggests that, had God not stepped in forcefully to alter their trajectory, the slaves would not have become a nation and the story of Israel would never have truly begun. This phrasing brings the story from the distant past closer to home. Real gratitude comes from the experience of having been personally saved. We need to understand and convey to our children that salvation is not a relic of the distant past, but that our own freedom is directly attributable to God’s wonders in Egypt. This reinforces the idea that the point is to teach about God’s actions, not the Israelites’ experience. Slavery serves only as the backdrop against which we learn to appreciate our freedom.

This message is, in fact, the foundation not only for one festival but for all of Torah: at Sinai, God’s identity as “the one who brought you out of Egypt” becomes the basis for God’s right to impose divine law. This connection is further expressed in the original setting from which avadim hayinu was taken, Deuteronomy 6. Here, the parent is commanded to teach about the exodus in response to a child asking, “What are these rituals, statutes, and laws that God commanded you?” This child is asking about the entire system of divine law, not the rituals of Passover, and yet the exodus is still the answer. The message is the same: we were in need and God saved us with mighty deeds—and, it adds, led us to the Promised Land and gave us the law.

Arami Oved Avi: My Father was a Wandering Aramean

Let’s turn now to the longest section of Maggid, an exegesis of Deuteronomy 26:5-8. This is the passage that begins with arami oved avi, “my father was a wandering Aramean,” in line with the third instruction we find in the Mishnah. The exegesis is written as a midrash, explicating phrase by phrase the biblical passage, which reads:

My father was a wandering Aramean. He went down to Egypt with meager numbers and sojourned there; but there he became a great and very populous nation. The Egyptians dealt harshly with us and oppressed us; they imposed heavy labor upon us. We cried to Adonai, the God of our ancestors, and Adonai heard our plea and saw our plight, our misery, and our oppression. Adonai freed us from Egypt with a mighty hand, with an outstretched arm and awesome power, and with signs and portents.

This text does indeed begin at the beginning, with Jacob and family settling in Egypt and then being enslaved by the Egyptians; and it does end at the end, with God striking the Egyptians with “signs and portents.” What is conspicuously absent again is the middle, including everything that we would typically consider the drama of the narrative: the fear and bravery of Moses’s family; Moses’s crisis of identity and flight from Egypt; God giving him his mission at the Burning Bush; and Moses and Aaron’s confrontations with Pharaoh and their own people. Even the plagues, which in Exodus are a prolonged battle of wills and wits, are only briefly noted.

Many commentators, both traditional and modern, have struggled with the question of why this passage is chosen as the text for interpretation instead of a more robust summary from elsewhere in the Bible, or even portions of the original text of Exodus 1-12. Some propose quite implausible theories. Joshua Kulp offers refreshing clarity in the Schechter Haggadah with a simple and practical explanation:

The passage was chosen because it is the briefest and yet still comprehensive passage in the Torah which tells the story of the descent to Egypt and the redemption. Such a short passage is prime material for Midrash, a literary genre which focuses on individual words or phrases and connects them to other portions of the Torah. Exodus 12, or any other part of Exodus, is too long, digressive and not as comprehensive.

In short, Kulp argues that the Rabbis’ goal was to simply present a single, adequate review of the exodus story for close reading. The limiting factor in the choice of text was that for the Rabbis, close reading means midrash, a style of interpretation that works through a biblical text phrase by phrase, and therefore requires a fairly concise base text as its focus. These considerations made Deuteronomy 26 the obvious choice for the Seder ritual. It would be impossible to read and interpret all of Exodus 1-12 within a single evening, while other summaries in the Bible are even briefer than the arami oved avi passage.

Kulp’s proposal is clearer and simpler than the alternatives, but it shares the basic assumption that this text is a less than ideal choice, that we should be telling a more complete version of these events, yet are saddled with one that leaves out key details. The distortions we find in how the story is told, with some elements described in detail and others passed over in silence, are an unavoidable but still unfortunate consequence.

I agree with Kulp’s assessment that other biblical reviews of the events of the exodus (there are, depending how we count, at least ten others) share the key features of the Deuteronomy passage. But I would argue that reading it in the context of these other passages actually reveals clearly what the Haggadah is doing and what it is not. It illustrates the distinction between recounting the exodus as a story of the Israelites’ triumphant escape from slavery, and using it to enumerate praises of God—precisely the difference between lesaper and lehaggid.

These lists come in various forms, from songs of praise to speeches urging Israel to show gratitude, to confessions of Israel’s ingratitude. Psalm 136, known as the “Great Hallel,” is simply a list of God’s wonders across the full range of biblical history. It begins with the creation of the heavens, then describes God striking the Egyptian first-born, bringing Israel out of Egypt, and drowning Pharaoh’s army, followed by God defeating other kings in the desert, and ultimately bringing Israel into the Promised Land. In Joshua 24, God speaks in the first person to highlight the wonders, including the exodus, God did specifically on Israel’s behalf; while Psalm 106, a prayer of confession, emphasizes that God did these wonders despite Israel’s ingratitude and frequent rebellions. All of these focus on God’s actions, whether presenting them as evidence of God’s might, God’s kindness, or God’s faithfulness.

Arami oved avi offers its own nuance on this theme. Originally a prayer of thanks to be said by Israelites bringing the first fruits of the Promised Land to the Temple, it describes in detail Israel’s descent, first to Egypt, then into oppression, and their cry for help. It describes Israel’s disgrace in order to frame God’s intervention as heroic, leading them up out of bondage, out of Egypt and back to the Promised Land, coming to their rescue in their hour of need, deepening the personal sense of appreciation and indebtedness. Even so, it is closely parallel to the other lists of God’s wonders. All of them recall the exodus from Egypt specifically to present it as the preeminent example of God intervening in history, dramatically and publicly, on Israel’s behalf. The only relevant elements beyond the list of God’s acts are Israel's need for them or response to them.

I want to emphasize how different this is from the original narrative in the book of Exodus. That text chronicles the human experience of slavery, following both the Israelites and the Egyptians, with a spotlight on Moses, Aaron, and Pharaoh. God’s role is marginal until the final scenes. These other texts, by contrast, tell us only what God did, and notes human roles only to highlight God’s role.

The most illuminating example, though, is Psalm 78, which explicitly declares that it is the fulfillment of the mandate in Exodus to “tell your children.” Here are the key lines:

We will tell the coming generation the praises of God and His might, and the wonders He performed. He established a decree in Jacob, ordained a teaching in Israel, charging our fathers to make them known to their children, that a future generation might know—children yet to be born—and in turn tell their children, that they might put their confidence in God, and not forget God’s great deeds, but observe His commandments. (Ps. 78:4-7)

The Psalmist is quite clear about both exactly what we must tell our children and why. When the Torah commands that we tell our children about the exodus, it is referring specifically and exclusively to the wonders that God did on behalf of the Israelites in their time of need. And the purpose of this commandment, of repeatedly recalling those wonders, is to ensure that the next generation, recalling those acts, keeps an unshakeable faith in God’s love and a devotion to God’s mitzvot. The alternative, the Psalm goes on to say, is also made clear in the Torah: the Israelites repeatedly lost that faith and rebelled during the desert journey, always with disastrous consequences.

And thus the picture comes into view in full clarity. It is true that arami oved avi, like the other reprises of the exodus across the Bible, tells a very different story than Exodus 1-12. But that does not make any of these versions a deficient fulfillment of the Torah's command, lehaggid. They are in fact fully in line with the lesson the Torah wants us to convey. Psalm 78 is literally the Bible’s prototype for how to properly fulfill it.

This is also the way almost the entire Haggadah approaches this command. It does not tell a tale that progresses from disgrace to praise, but one that includes only these two elements: we were in a place of disgrace and God redeemed us. And the point of this explanation is not the story itself but the lesson it teaches: God came for us in our time of need and did wondrous, astonishing, supernatural things on our behalf to bring us to freedom and make a place for us in the world. What we must do in the present is be thankful for those acts, acknowledging that they were done not just for our ancestors, but for us. Our devotion to God, which we show by performing the Passover ritual, celebrating the festival, and observing all of God’s laws, flows directly from that awareness.

This framing opens up a whole new way to read the deeply evocative but enigmatic statement that concludes Maggid: “In every generation we must see ourselves as if we personally left Egypt.” Many explanations of this line take it to mean as if we had personally been enslaved, and this can be a springboard for cultivating empathy for all who are oppressed. But the Haggadah’s focus is not on slavery; it is on coming out of Egypt. Here too, slavery recedes to the background and the exodus is what matters. It is the exodus, the exhilaration of being carried to safety in God’s hands, that always needs to feel like it just happened to us.

This is the real point of the Seder ritual, for the exodus to be happening in what we can call the Eternal Present. Like Moses’s paradoxical claim that all future generations stood/stand at Sinai, the Seder is meant to make us feel for a moment that we are there on the banks of the sea, living that ecstatic moment of finally knowing that we are fully and irrevocably free. Look back and you will notice that the crucial claims in the Haggadah are in the present tense. If God hadn’t saved us, we today would still be slaves. In every era, including our own, there is an enemy pursuing us and, true to God’s promise, God saves us from their hand. Our freedom now is thanks to the exodus; we are kept safe now because of God’s promise; and when we see that, when we really get it, we will be able to see ourselves as if we now are standing on the banks of that sea, that God’s salvation happened to us personally and thus makes a direct claim on each of us. We did not all experience slavery, but we have all been saved from it.

And the ritual prescribes that we respond to that awareness just as we did the first time, with an instinctive and unrestrained outpouring of song. This is the moment of transition in the Seder: We go from the story of our disgrace to an intense song of praise filled with the intensity of those who have just escaped oppression. We, in this moment, know that we owe all we have to God’s salvation, and therefore cannot help but begin pouring out songs of thanks. If we have done Maggid properly, Hallel will simply burst forth. This is where the night reaches its apex, when we are ready to relive the joy of salvation and to sing praise to God with the same intensity and gratitude as the Israelites who sang at the sea.

I have tried to demonstrate that the reason we often find it hard to engage meaningfully with the Haggadah is that the text is focused on a fundamentally different purpose than the one we typically bring to the table. Part of my goal has been to unlock the mystery in this familiar text, so we can see it anew and read it on its own terms; I have also tried to reclaim this earlier mission, which has been largely displaced by sipur. I would not wish to argue that storytelling should be removed, that we hold back from discussing slavery, from remembering Moses, Miriam, and Aaron. Sipur enables us to include and engage children of all ages by filling in the missing narrative—playacting Moses’s showdown with Pharaoh, marching around like Israelites in the desert, and making the plagues colorful and silly. In this way our children are engaged, and they come to know the story as their own. And the challenge of finding new layers of this story adds richness and creativity to the ritual.

But I also hope I have convinced you that the story is not an end in itself. A ritual’s sole function cannot be limited to retelling a familiar story, even if it is a great story. Even if it is our story. The goal of the Seder ritual is for us to notice and to celebrate how far we have come; and to move us to joy, to gratitude, and ultimately, to hallel—to praising God.

So, the Seder can be a time for telling wonderful stories or for reflecting on evils yet to be overcome. But don’t worry if you don’t get to the whole story. Don’t fret about its moral ambiguities. There is a time for self-critique, a time for feeling the weight of the world’s burdens. But not on this night. The Seder is not the night to relive the suffering of being slaves. It is the night to relive the joy, the elation of that moment when we left slavery behind to embark on a new journey, full of promise and possibility. Looking at the open vistas around us, knowing that we were once slaves: How can we keep from singing?

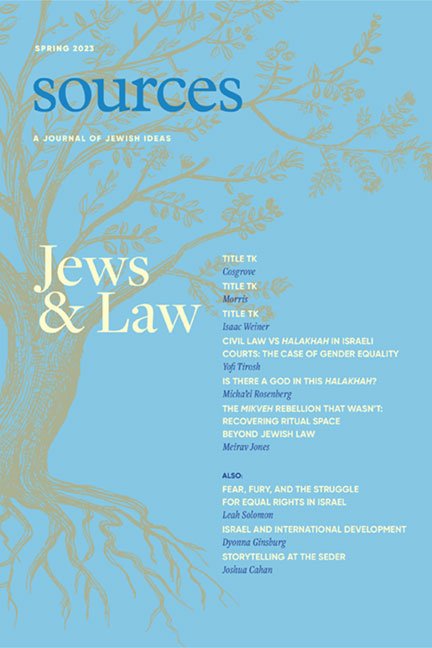

This article appears in Sources, Spring 2023.