Is There a God in This <em>Halakhah</em>?

JEWS AND LAWMicha’el Rosenberg

Micha’el Rosenberg is a member of the faculty at Hadar.

Recently, I have been bothered by the question of how to feel God’s presence in Jewish law (halakhah). For years, I engaged in debates with friends, colleagues, students, and teachers about halakhah. We would argue about both the particulars of specific questions and about the nature of halakhah more generally, without being bothered by the apparent absence of God in our conversations. We were interested in the practical consequences, and how our interpretive and philosophical differences led us to different answers. Those questions are still important to me; they are the ones with the most direct impact on how traditionally observant Jews live our lives, on questions of who is included and who is excluded, what counts and what does not. This essay is not a withdrawal from that grand debate.

But I have come more and more in the last few years to be dissatisfied with my previous contentment to leave questions about God and theology, for the most part, on a parallel track to those about halakhah and lived Jewish experience. This discontent derives not from some principled philosophical position, but simply from a sense that something is off when our halakhic thinking and our God talk are siloed.

Halakhah, in theory and in practice, is grounded in the Torah—if, in many cases, via long and winding roads through inherited traditions, rabbinic statements, medieval and early modern debates, and contemporary applications. For those of us who perceive the Torah as the word of God, it makes sense that God’s presence should be palpable in both our learning and our living out of halakhah. Put another way: If halakhah is the Jewish understanding of divine law, then surely the divine should be visible within it.

Yet this is not the case. It is not the case in theory or in practice. In practice, one can read pages and pages of any collection of responsa (answers to halakhic questions) without finding an explicit reference to God or God’s will. I assume that for most of these authors, this omission is a sign not of God’s absence, but rather of God’s omnipresence; it is so obvious to these poskim (decisors) that we are trying to ascertain God’s will when, for example, figuring out whether heating food in a microwave counts as cooking it, that there is no need to say so. Still, the omission, however understandable, has costs. For many of us who imbibe this literature, it is all too easy to forget that piece of the work; when a responsum by, say, the Rashba is entirely comprehensible without a theological underpinning, then perhaps the theology is indeed unimportant.

The omission of God from halakhic thinking is just as regrettably common in theories of halakhah. Though there is a whole library of works written on the conceptual underpinnings of halakhah—articles and books trying to couch Jewish law in the language of secular legal theory, or arguing over rules of its interpretation—they rarely invoke God or theology. When they do, they tend to do so in passing, as an unexamined assumption. Halakhah is “God’s will,” they might say in an introductory paragraph. They do not return to this assumption, and typically, the remainder of the argument proceeds without any mention of God at all.

The problem cuts across ideological and theoretical commitments. The last century has seen much debate about the source of halakhah’s authority. Though this intellectual history demands far more nuance than I can give it here, for the most part, the actors in these arguments fall into one of two camps, both with origins in secular legal theory. The positivists assert that law in general, and halakhah in particular, derives its authority from a foundational principle (often referred to, following the work of Hans Kelsen, as a grundnorm), which sets the terms of all debate going forward. This foundational principle is not innate in the world, but rather is, at some point in history, posited. In U.S. law, for example, this grundnorm is the Constitution; for Jewish positivists, it is (typically) the Torah.1

Opposed to the positivists are the natural lawyers, who contend that law is fundamentally grounded in nature. If you know how to properly read the world, say the natural lawyers, you can discern “The Law” from its workings.

More recently, a third school of thought has taken up space in this debate, at least in the part of the Jewish world I primarily inhabit. Inspired by the thinking and teaching of my own teacher, Rabbi Elisha Ancselovits, halakhic consequentialists focus not on law’s authority, but on its consequences. Halakhic sources, in this mode of thinking, are all working out the costs and benefits of possible responses to complex situations, in order to choose the best option.

Irrespective of which of these three tacks one takes with regard to halakhah, thinking about God as essential to this project is not obvious. This is clearest for those in the camp with which I associate, the consequentialists. Essentially, halakhic consequentialism is a Torah-grounded form of utilitarianism. By definition, it requires reference to Torah (in the sense of the Hebrew Bible and the long rabbinic tradition that interprets it), but it is not fundamentally dependent on an appreciation for God as the author of that Torah or the wisdom that flows from it. This is a criticism I regularly hear from colleagues who object to halakhic consequentialism, and it is one I take extremely seriously.

It is not, however, unique to this approach. Consider halakhic positivism, which is the approach most likely to require a God-consciousness to be coherent. After all, in this halakhic worldview, halakhah’s authority flows directly from the Torah existing as a posited source of authority. Rabbi Joel Roth makes the point clearly and succinctly in his positivist exposition of halakhah, The Halakhic Process. According to Roth, the grundnorm of halakhah is this: “The document called the Torah embodies the word and will of God, which it behooves man [sic] to obey, as mediated through the agency of J, E, P, and D, and is, therefore, authoritative.”

This is coherent, and it would appear to depend completely on the acceptance of the Torah as, in Roth’s words, “[embodying] the word and will of God.” After all, why else should anyone take seriously the Torah as an obligating text?

Roth continues, however; the immediate next sentence is: “An alternative possible formulation might be: The document called the Torah embodies the constitution promulgated by J, E, P, and D, which it behooves man [sic] to obey, and is, therefore, authoritative.”

This alternative formulation leaves out any mention of God. Following the Documentary Hypothesis, according to which the Torah is a composite of four human-authored strands, it attempts to articulate a reason for observing halakhah without any divine intervention. When juxtaposed with the first version—that the obligating power of the Torah devolves from its divine origins—this godless halakhah might seem less than compelling. The origins of legal positivism in secular legal theory make clear that this is not the case. One need only think about Constitutional originalists in American jurisprudence, who valorize the Constitution as the foundational and binding text of U.S. law without ever claiming that the Constitution is, in any sense, divine in origin. There are all sorts of reasons why one might accept the notion of a non-divine binding grundnorm—legal stability, communal acceptance, cultural norms—without assuming God’s will has anything to do with the matter.

So it is entirely possible to imagine halakhah without God, irrespective of the legal theory one might assign to explain it. More to the point, we need not imagine it, because shockingly little of either halakhah (by which I mean the primary sources that compose the legal body) or meta-halakhah (the philosophical tracts, written primarily in the last century, which try to explain the why and how of halakhah writ large) ever references God in a serious and substantive way.

Those who share my desire for halakhah to have some kind of explicit relationship with the divine must articulate a reason and a mode for God’s involvement in our thinking about this subject. Why and how might God be essential to halakhic thinking?

It might be helpful to think about a way in which God’s involvement in halakhic thinking complicates the discourse. To the extent that halakhic texts—and especially the biblical passages that undergird entire halakhic conversations—present ethical problems for contemporary readers, a close association between those halakhic texts and our perception of God creates a theological problem. A sensitive reader who is appalled on ethical grounds by some law in the Torah will naturally ask: What kind of a God would want this? As Rabbi Rachel Adler asks in Engendering Judaism, “Do the passages concerning the trial by ordeal of the suspected adulteress or the characterization of homosexuality as an abomination and a capital crime really embody the word and will of God?”

Love Jewish Ideas?

Subscribe to the print edition of Sources today.

The ethical challenge of tightly imbricating one’s theology and one’s approach to halakhah might naturally lead to the alternative, i.e., disentangling the two. Perhaps this explains why Roth, in his formulation of the grundnorm of halakhic thinking, provides his second, God-free option.2 This attempt to fully disconnect halakhic discourse from theology, however, generates its own problems. As Adler puts it, directly responding to Roth’s attempt to provide such an alternative for grounding halakhah: “What makes J, E, P, and D deserving of our unconditional obedience?” As I noted above, we have many examples of legal thinkers, Jewish and not, who rely on a claim of a posited foundational principle—a grundnorm—that is not divinely provided. But when the rubber hits the road, that is, when the system produced by that human-authored foundational principle leads to a ruling that strikes the reader as fundamentally unethical, why should those readers stay committed to the system?

In his recent book, Divine Will and Human Experience, Rabbi Aryeh Klapper likewise addresses the challenge posed by Adler. Klapper writes: “We all censor Torah. We all have rigid rules about what Torah cannot mean, and tools to make sure it means something else.” This censorship, often unconscious, tries to narrow the gap between, on the one hand, assumptions about right and wrong so core to our thinking that we cannot imagine the world otherwise, and on the other hand, first-read interpretations of the Torah that are at odds with those assumptions.

I do not know why Adler did not discuss this kind of “censorship” as a way of responding to the challenge, but I can imagine at least one reason: It sounds impious. To “censor” the Torah does not sound like the action of a faithful reader and actor, committed to living out the ideals and guidance of a divinely-given text. If you believe that the Torah is the word of God, why—and how!—would you censor it?

Responding to this question requires that we distinguish between the Torah as sacred wisdom and the Torah as sacred authority. The latter form of Torah belongs to a fundamentally positivist approach; if God is the Creator to whom we necessarily owe allegiance, if God is all-powerful and can therefore demand allegiance, etc., then we have an obligation to observe the Torah, irrespective of the wisdom of its content. It has authority. The former, by contrast, is fundamentally congruent with a theologically-grounded halakhic consequentialism: the Torah obligates us because, as the word of God, it contains perfect wisdom. We are obligated to it, not because of God’s authority, but because of God’s wisdom.3

If one is operating in a starkly positivist mode, focusing on God’s authority, then one has only two options: One can submit to that authority, or one can dismiss it, whether by framing one’s actions as rebellion vis-a-vis God, or by rejecting the claim that the Torah indeed reflects God’s will.

If Torah’s obligatory power derives from its wisdom, however, our options are greater. Rather than submitting to an ethically troubling command or dismissing that order, theologically-grounded halakhic consequentialists might begin from a place of confusion and disorientation, but they will not end there. The dysphoria resulting from a conflict between their deeply held ethical convictions and a word of God that seems to contradict them must and will lead to reinterpretation.

I cannot stress enough: That reinterpretation can take two forms. It can lead to the reader’s reassessment of their own assumptions; after study and contemplation, what initially seemed an unshakable ethical assumption turns out to be not so straightforward. The initial reading of the Torah challenges and effectively undermines the reader’s assumptions—not through the brute force of authority, but through the illuminating effects of divine and perfect wisdom.

The reinterpretation can also take the form of new, better understandings of Torah writ large. In some cases, the process of deepening one’s learning in order to resolve the contradiction between writ and principle challenges the reader’s starting assumptions; at other times, it leads to an interpretation of the text that, though it was not initially obvious, legitimately comes to appear to the reader as a stronger reading of the text.

In a deep way, this second form of reinterpretation—new understandings of Torah that result from the disjunction between what we assume about both ethics and the meaning of the text—is precisely what Klapper describes when he states that we all “censor” the text. The “rules about what Torah cannot mean, and tools to make sure it means something else” are a part of the interpretive toolbox that allows us to achieve better understanding.

There is a rhetorical difference, however, that I believe reflects a significant theological and meta-halakhic difference. Both the language of “censorship” and the adjective Klapper uses to describe those rules (“rigid”) have a decidedly impious connotation, and one that is not coincidental. Klapper takes a moderate approach to this censorship: “We should come to Torah with rigid assumptions, especially moral principles…But one should not come to Torah with very many such assumptions” (68, emphasis added). The implication is that the “censorship” and “rigid rules” that allow for it are necessary but unfortunate impositions on an otherwise pure relationship with Torah.

For the theologically-grounded halakhic consequentialist, the gap between “censorship” and “interpretation” could not be greater. The latter is not an impious, temporary deviation from a faithful engagement with Torah for the sake of the greater good. It is, rather, the deepest expression of a pious learning of Torah. Understood thus, the disconnect between what the Torah seems to say and what our ethical intuitions tell us is a problem precisely because we are so committed to the notion that God is the ultimate author of these ideas, and that God is good.

In this sense, the reinterpretation of a halakhic text that, after wide and deep learning of the topic and careful consideration of all its implications, is a re-placement of authority back in the hands of God. A good example of this sort of reinterpretation is Rabbi Yehuda Amital’s well-known response to the question of what someone who is starving should do when faced with a choice between eating food explicitly forbidden by the Torah and human flesh, which is never expressly forbidden by the Torah:

It seems obvious to me that God does not want man [sic] to eat human flesh. The Torah fails to mention that the eating of human flesh is forbidden, not because it is permitted, but because certain things are so obvious that it is unnecessary for the Torah to state them. (Jewish Values in a Changing World)

Amital frames his dismay at a possible, but to his mind unquestionably wrong, ruling as theological in origin—God could not want this. This impossibility, however, leads neither to submission to a first-read interpretation of the text, nor to its dismissal. Instead, he reinterprets: The omission of a prohibition on eating human flesh is because it was too obvious to state.4 A proper reading of the Torah clearly forbids eating human flesh, even if a “plain-sense” reading finds no such injunction.5

There is good reason to be nervous about such an approach. What is obvious to me might not be obvious to you. We could be wrong about our understanding of what God wants of us. Despite our extensive efforts to get to the bottom of a topic, we might miss the mark—whether in our reading of the halakhic texts or of the ethical stakes.

But this is a necessary danger of any approach. We should not fool ourselves into thinking that “literal” readings are less fallible. That, too, is the result of interpretive assumptions that may be—and in my view, are—wrong. The question is not which approach is most likely to be right, but rather, which approach is most faithful.

There is perhaps an irony here, namely, that the more faithful approach of constant attunement to the presence of God in the halakhic conversation can lead one to more innovative and pioneering interpretations. For someone who thinks of halakhah as a fundamentally human project, disjunctures between our readings of texts and our ethical intuitions can lead only to submission or rejection. The theologically-grounded halakhic consequentialist, by contrast, can accept neither of these options and instead might end up with new and surprising readings. These readings are new and surprising precisely because they are grounded in a deeply-felt sense that the halakhic reader’s job is nothing less than to discern God’s will. That is a task that requires both humility and bravery, fealty as well as innovation.

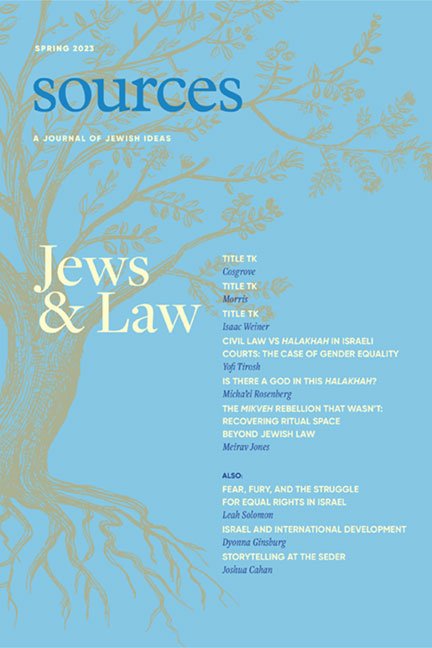

This article appears in Sources, Spring 2023.

Endnotes

1 Rabbi Gordon Tucker critiques this formulation of Judaism’s grundnorm (Gordon Tucker, “God, the Good, and the Halakhah,” Judaism 38:3 [1989]).

2 I assume that this second formulation is motivated as well by the recognition that many contemporary Jews, including many who would self-define as halakhic, are less confident in their theology than in their commitment to Jewish law.

3 I am inspired here by Moshe Simon-Shoshan’s distinction between being “in authority,” i.e., holding an official position of power, and being “an authority,” that is, holding power by virtue of one’s wisdom (Simon-Shoshan, Stories of the Law: Narrative Discourse and the Construction of Authority in the Mishnah [Oxford University Press, 2012], 65 and 131). He applies the distinction here not to God but to rabbinic sages.

4 This interpretation has the advantage of being similar to (though not identical with) a common interpretive technique found in the Talmud (lo mibaya ka’amar).