How Do You Say <em>Tikkun Olam</em> in Hebrew? Israel and International Development

PRESCRIPTIONDyonna Ginsburg

Dyonna Ginsburg is the CEO of OLAM, a network of Jewish and Israeli organizations working in the fields of global service, international development, and humanitarian aid.

There’s a well-known one-liner about an American Jew visiting Israel for the first time. Shortly after arriving in the Jewish state, the visitor turns to a local and asks: “How do you say tikkun olam in Hebrew?”

Tikkun olam, translated literally as “repair of the world,” is understood here loosely as a Jewish responsibility to broader humanity. When this joke is shared by American Jewish progressives, it is a bit of self-deprecating humor celebrating the widespread emphasis in liberal American Jewish life on tikkun olam. When told by conservatives, it’s a questioning of tikkun olam’s authenticity, as a Hebrew phrase and as a Jewish priority.

No matter who tells it or what they think about tikkun olam, this is a joke told by American Jews about American Jews. Its humor rests on the pervasiveness of the idea of tikkun olam in American non-Orthodox Judaism and, more broadly, in American culture, where even prominent non-Jewish politicians, such as Barak Obama and Hillary Clinton, regularly invoke the term.

Yet, the setting of the joke is also important, as it reveals an assumption American Jews too often make about Israel. Because it imagines an American Jew posing the question to an Israeli Jew, it implies that universalist values are the exclusive domain of American Jewry and largely alien to Israeli identity. At best, tikkun olam is perceived as peripheral to Israel; at worst, antithetical to it. A variation on this one-liner makes this point even clearer: “There are two types of Jews: those who pursue tikkun olam, and those who speak Hebrew.”

I have encountered these assumptions countless times when speaking with American Jewish audiences about Israel’s humanitarian work abroad. I find that American Jews perceive of Israel’s contributions to disaster relief, agriculture, health, and other global challenges either as window dressing—a source of pride, yet trivial relative to other aspects of Israel’s identity—or as whitewashing, a cynical ploy to divert attention away from Israel’s treatment of Palestinians. In both cases, the assumption is that this work lacks significant meaning.

As someone who pursues tikkun olam and speaks Hebrew, I don’t find this funny. Since making aliyah from the United States 20 years ago, I have spent the better part of my career working on issues of social justice in Israel and around the world. For me and for countless other Israelis, Zionism and universalism are deeply intertwined and mutually reinforcing. In our eyes, the State of Israel presents an unprecedented platform for the Jewish people to do good in the world. Although today’s reality is far from this aspirational vision, I am deeply committed to its actualization.

It might surprise many American Jews to learn that the term tikkun olam—which was first used in early rabbinic literature and the contemporaneous Aleinu prayer, and subsequently gained new meaning in Lurianic Kabbalah—was revived by Zionists in mandatory Palestine before it was used by American Jews. Indeed, the earliest recorded usage of the phrase tikkun olam in the 20th century was among members of the Second Aliyah (1904–1914). The phrase did not make its modern debut in the United States until World War II.

That said, the term tikkun olam has not yet gained serious traction in Israel. Early Zionist thinkers preferred the language of chevrat mofet (model society) and or lagoyim (a light unto the nations) to describe the values and efforts that we might today call tikkun olam. When Israelis do invoke tikkun olam nowadays, it is generally in the context of addressing American Jews, as was the case with Israeli President Reuven Rivlin’s remarks to the Jewish Federations of North America’s General Assembly in 2018: “The Zionist vision has always strived for Israel to be an essential and inspiring member in the family of nations, rooted in the Jewish notion of tikkun olam.”

But the fact that Israelis use different language to express their universalist values does not mean these values are absent from the Zionist ethos. Indeed, for many early Zionist thinkers, universal principles were essential to their vision of a Jewish state. For example, both the Religious Zionist Rabbi Abraham Isaac Kook and the Labor Zionist A.D. Gordon envisaged Israel as a laboratory for justice and understood the Jewish people’s national liberation as interconnected with the liberation of the rest of humanity. Israel’s early politicians, in turn, grounded some of their concrete policy decisions in a universalistic vision. One of the clearest examples of the latter was David Ben Gurion and Golda Meir’s choice to devote significant state resources to international development and bilateral aid in Israel’s early years.

The Launch of Israel’s International Development Agency

In 1958, then Foreign Minister Golda Meir travelled to Africa for the first of several state visits to the continent. She had been invited by Ghana’s new leaders to attend the celebration of the first anniversary of its independence, and on her trip, she also visited Liberia, the Ivory Coast, Senegal, and Nigeria, where she met with leaders of anti-colonial liberation movements. Deeply moved by the challenges they faced, Meir returned home convinced that Israel should play a significant role in supporting developing countries in the areas of health, education, nutrition, gender equity, and more. She felt a sense of kinship with the decolonized countries of Africa and Asia because she understood Israel to be a decolonized country—a view shared and reinforced by many African leaders at the time. As she wrote in her 1973 memoir, My Life,

Like them, we had shaken off foreign rule; like them, we had had to learn for ourselves how to reclaim the land, how to increase the yields of our crops, how to irrigate, how to raise poultry, how to live together and how to defend ourselves. Independence had come to us, as it was coming to Africa, not served up on a silver platter, but after years of struggle, and we had had to learn—partly through our own mistakes—the high cost of self-determination. In a world neatly divided between the haves and the have-nots, Israel’s experience was beginning to look unique because we had been forced to find solutions to the kinds of problems that large, wealthy, powerful states had never encountered.

Israel’s Foreign Ministry launched the Agency for International Development Cooperation—known by its Hebrew acronym, MASHAV—later that year, in direct response to Meir’s trip to Africa and the relationships she cultivated there.

Across the Atlantic Ocean, President John F. Kennedy created the comparable United States Agency for International Development (USAID) in 1961—three years after the establishment of MASHAV. America had previously run foreign aid programs, but this was the first time it had a single agency dedicated to that purpose. With the US embroiled in the Cold War, Kennedy saw supreme strategic significance in cultivating relationships with the non-aligned, newly independent states of Africa and Asia. He also spoke to Congress about the sense of responsibility that comes with having plentiful resources: “there is no escaping our obligations…as the wealthiest people in a world of largely poor people, as a nation no longer dependent upon the loans from abroad that once helped us develop our own economy.”1

In stark contrast to the United States, Israel was not wealthy when it launched its own international development agency. The state’s early years were punctuated by two wars and characterized by a massive influx of immigrants, soaring inflation, and a large deficit. My mother, born in 1951 on a kibbutz, remembers the “austerity period” of state-imposed food rations of 1,600 calories per day. Officially considered a developing country, Israel relied on overseas Jewish philanthropy and bilateral aid for its very survival.

Under these circumstances, it would have been entirely justified for Israel’s early political leaders to focus all their efforts inward. Yet they chose to simultaneously reach outward and support other developing countries.

“A Historic Privilege and a Duty”

In their writings, both David Ben Gurion and Meir spoke honestly about a wide range of motivations behind the launch of MASHAV. Surrounded by hostile neighbors, Israel needed all the friends it could muster. Ben Gurion and Meir were keen to ameliorate Israel’s diplomatic isolation, gain support from the United Nations, and bolster the country’s teetering economy. They hoped to influence the newly independent African and Asian states to side with Israel and exert pressure on the Arab world to reconcile with the Jewish state.

The two also saw this as an opportunity to position Israel vis-à-vis the United States and Europe. By punching above its weight in the realm of international development, the fledgling State of Israel could distinguish itself among other developing countries and gain the respect of the world’s superpowers.

But Ben Gurion and Meir insisted this was not mere realpolitik. In the annual missive he wrote for the 1960 government yearbook, Ben Gurion stated: “We must not, however, assess the importance of our relations with the peoples of Africa and Asia from the economic and commercial points of view alone.”2 Similarly, in My Life, Meir rejected the claim that Israel did this work solely for its own gain: “Did we go into Africa because we wanted votes at the United Nations? Yes, of course that was one of our motives—and a perfectly honorable one—which I never, at any time, concealed either from myself or from the Africans. But it was far from being the most important motive.”

Notably, in its early years, Israel did not make its support to other countries conditional on political returns. Several countries, such as India, Pakistan, Somalia, and Indonesia, participated in Israel’s development programs even though they did not formalize relations with the Jewish state.

Ben Gurion’s Vision

Ben Gurion’s annual missives to the state’s citizens functioned much like the State of the Union address in the U.S., giving him an opportunity to articulate a grand vision for the country. Ben Gurion believed he was living in historic times, both for the world and for the Jewish people. In the 1960 missive quoted above, he called Israel’s support for emerging states in Asia and Africa a “great historic privilege—which is therefore also a duty.” The following year, his entire 34-page missive, titled “Towards a New World,” addressed Israel’s role in international development, inspired by the 17 African countries that had attained independence in 1960.

Like Meir, Ben Gurion drew parallels between Israel’s struggles under British colonial rule and those of other decolonized states. Witnessing the vast changes afoot in the world, he talked about a “new and unprecedented era in the annals of mankind,” characterized by human liberation, in which “all peoples, no matter what their colour, race or culture, will be members in the family of man, sovereign and free.” More than in any previous era, Ben Gurion believed conditions were ripe for global cooperation, peace, and security. With remarkable prescience, he insisted that “even the Cold War is but a passing phase.”

As Ben Gurion expressed it in his 1961 missive, one of the main threats to this audacious vision was the sizable gap between rich and poor countries. And it was precisely here, he believed, that Israel had a unique role to play. At the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa, Israel’s liminality—geographically, culturally, and economically—made it a suitable bridge. He attributed the popularity of MASHAV’s training programs to the fact that other countries saw Israel as relatable: “It is not because she [Israel] is powerful and great, rich and generous, but because the new states regard her as a very suitable and instructive specimen of a country that is trying, with no little success, to solve problems that concern old and new in Asia and Africa.”

Given its relatively small budget, Israel’s primary methods of global assistance had to be different from those of America or Europe. Rather than issuing large grants or loans, Israel focused on sharing homegrown knowledge. In this way, Israel’s support for other developing countries did not come at the expense of addressing its local needs, but rather, was an extension of its investments in its own development:

Some doubt whether it is in Israel’s reach to render a sizable measure of help. She is still, and for years will be, herself in need of aid from world Jewry and support from her friends abroad. No other country has such serious problems of security…Our scant resources are not enough for existence and urgent development in Galilee, the South and the Negev, for the consolidation of new settlements and swifter strides towards economic independence. What then, can Israel contribute to the new countries in Asia and Africa and how? The simple and truthful answer is by what she does for herself in her own country.

By investing in agriculture, disease prevention, education, and other issues of social welfare, Israel could address its own needs, and simultaneously become a “model and an example” for others. In 1961, Ben Gurion imagined Israel not only as a laboratory for finding solutions to global issues, but as a demonstration site as well. He championed inviting people from other countries to enroll in Israeli institutions of higher learning to “learn how feasible such changes are, how profitable, and how to bring them about at home.”

Ben Gurion saw this work as both strategically significant and a moral calling: “And we Jews in our homeland must ask ourselves: Can Israel assist in the progress and development of Asia and Africa? For Israel, it is both a moral and a political issue, and from both aspects there is no doubt that Israel must look upon such aid as a historic mission, as necessary for Israel as it is beneficial to those we help.” He grounded this work in Jewish values like “love for the stranger and the sojourner” and employed messianic language to convey its importance. Making the case for Israel to serve as a place where other countries could learn solutions to global challenges, Ben Gurion cited three verses from the book of Isaiah that otherwise “seem disparate”: the ingathering of the exiles (43:5-6), the Jewish people as a “light unto the nations” (42:6), and the dawn of world peace (2:4). Like puzzle pieces that only make sense when you put them together, Ben Gurion believed these three verses cohered in a reality in which the modern State of Israel would share with others the lessons it had learned about immigrant absorption and, in so doing, bring about world peace by bridging the gaps between low-income and high-income countries. He saw Israel’s population boom, coupled with MASHAV’s early successes, as proof that “the footsteps of the Messiah are faintly to be heard even now.”

Ben Gurion’s use of messianic language in this context is consistent with his writings elsewhere. His messianism, however, was neither religious nor eschatological. As the scholar of religion R.J. Zwi Werblowsky explained, Israel’s early political leaders “did not think in terms of Armageddon, or a heavenly Jerusalem descending from above, or the ‘son of David’ riding on an ass, but rather of civil liberties, equality before the law, universal peace, all-around ethical and human progress, the national emancipation of the Jewish people within the family of nations, and so on.”

For Ben Gurion, this messianic vision defined the Jewish people. He saw this vision as containing both universalistic and particularistic aspects and believed that the only way for the State of Israel to survive would be for it to fulfill this vision in its entirety:

It is the messianic vision, which has lived for thousands of years in the heart of the Jewish people, the vision of national and universal salvation, and the aspiration to be “the covenant of the people” and a “light unto the nations,” that has preserved us to this day, and only through loyalty to our Jewish and universal mission will we safeguard our future in the homeland and our standing among the nations of the world.

By using prophetic and messianic language to describe Israel’s mission, Ben Gurion attempted to unite religious and secular Jewish Israelis around a shared vision for the state and to ground the Zionist project in Jewish tradition. As the political scientist Michael Keren argued, this language also enabled Ben Gurion to connect with American Jews, who were citizens of a country “equally permeated by messianic ideals.”

It's worth noting, as well, that for American Jews struggling with allegations of dual loyalty, Ben Gurion’s messianic vision offered a solution. Seen in this light, supporting Israel was not an abandonment of universalism, but an embrace of it, and an extension of America’s own commitment to peace, justice, and democracy.

Ben Gurion penned his rousing words about Israel’s global responsibilities during the heyday of the country’s investments in international development, from the late 1950s to early 1970s. Within a few short years of MASHAV’s launch, Israel became a world leader in supporting newly independent states in Africa and Asia. By 1964, the ratio of Israeli international development experts to the total population was twice that of the OECD average, second only to France. By the end of the 1960s, Israel’s bilateral aid budget, while small in absolute terms, was comparable to that of the world’s largest and most developed countries when seen as a percentage of its GDP.

Unfortunately, this period was short-lived. Under pressure from the Arab world following the 1973 Yom Kippur War, all but four African countries cut ties with the Jewish state. In Israel, this was perceived by many as a betrayal of Israel’s friendship. As a result, internal political and public support for the country’s international development program plummeted. Within a two-year period, MASHAV experienced a drop of over 50 percent in its operational budget. It has never recovered.4 Much of the development activities that Israel has been able to continue have been financed through third parties.

Despite this permanent downshift, many people in Africa and Asia still remember Israel’s development work in the 1950s, ’60s, and early ’70s. While visiting Ethiopia, I met countless individuals who, upon learning that I am Israeli, shared fond memories of friends and relatives who had participated in MASHAV programs back in the day. I have had similar experiences in Nepal. In these countries, Israel’s early investments in international development left a lasting impression that seems to predispose people to regard Israelis favorably.

Love Jewish Ideas?

Subscribe to the print edition of Sources today.

Golda Meir’s Hindsight

Writing with hindsight after the 1973 rupture, Meir responded in My Life to an Israeli public disillusioned by MASHAV’s diplomatic failures, by presenting a view of statecraft as a long game:

“It was all a waste of money, time and effort,” they say, “a misplaced, pointless, messianic movement that was taken far too seriously in Israel and that was bound to fall apart the moment that the Arabs put any real pressure on the Africans.” But of course, nothing is cheaper, easier or more destructive than that sort of after-the-fact criticism, and I must say that in this context I don’t think it has the slightest validity. Things happen to countries as they do to people. No one is perfect and there are setbacks, some more damaging and painful than others; but not every project can be expected to succeed fully or quickly. Moreover, disappointments are not failures, and I have very little sympathy indeed for that brand of political expediency that demands immediate returns.

But, more importantly, Meir insisted that Israel’s development program was a manifestation of the country’s deepest values: “We did what we did in Africa not because it was just a policy of enlightened self-interest—a matter of quid pro quo—but because it was a continuation of our own most valued traditions and an expression of our own deepest historic instincts.” And, she argued, in the realm of values, actions have intrinsic worth even if they do not yield all of the intended results:

More than anything else that program typifies the drive toward social justice, reconstruction and rehabilitation that is at the very heart of Labor Zionism—and Judaism... For me, at least, the program was a logical extension of principles in which I had always believed, the principles, in fact, which gave a real purpose to my life. So, of course, I can never regard any facet of that program as having been “in vain,” and equally I cannot believe that any of the Africans who were involved in it, or reaped its fruits, will ever regard it in that light either.

Meir identified strong parallels between Jewish experiences of oppression and those of other peoples around the world. Grounding her position in Zionist thought, she cited a passage from Theodor Herzl’s 1902 treatise, Altneuland, that interpreted Jewish experiences of suffering as a charge to help others:

There is still one other question arising out of the disaster of nations which remains unresolved to this day, and whose profound tragedy only a Jew can comprehend. This is the African question. Just call to mind all those terrible episodes of slave trade, of human beings, who merely because they were black, were stolen like cattle, taken prisoner, captured and sold. Their children grew up in strange lands, the objects of contempt and hostility because their complexions were different. I am not ashamed to say, though I may expose myself to ridicule in saying so, that once I have witnessed the redemption of the Jews, my people, I wish also to assist in the redemption of the Africans.

Herzl’s passage echoed an essay written by the contemporaneous pan-Africanist leader, Edward Wilmot Blyden, written four years earlier, which argued that Jews and Africans were allied by a “history almost identical of sorrow and oppression” and asserted that “Zionism…is similar to that which at this moment agitates thousands of descendants of Africans in America anxious to return to the Land of their Fathers.”

As a socialist, a Zionist, and a Jew, Meir considered it a duty to oppose racial discrimination and oppression. She believed that Israelis—scrappy, informal, and willing to roll up their sleeves—could establish a new paradigm for partnership between white foreigners and local communities of color: “[African leaders] were anxious to meet and work with other Israelis. They were not used to white men who labored with their own hands or to foreign experts who were willing to leave their offices and work at the site of a project.” She insisted that local communities be consulted and that projects meet authentic needs:

We set up three basic criteria for our program, and I think it is not immodest to claim that even these criteria were a new departure. We asked ourselves, and the Africans, three questions about each proposed project: Is it desired, is it really needed, and is Israel in a position to help in this particular sphere. And we only initiated projects when the answer to all three questions was yes, so the Africans knew that we didn’t regard ourselves as being able, automatically, to solve all their problems.

Despite Meir’s insistence on partnership and local agency, she was sometimes guilty of using neocolonialist tropes herself. Adopting language that we would now label “white saviorism,” Meir spoke of Israel as the teacher and African countries as students. Similarly, Ben Gurion unabashedly affirmed the superiority of Western culture, even as he asserted that all human beings were equal.

In this way, Meir and Ben Gurion were a product of their time. I can’t help wishing they would have been ahead of the curve here, too. Indeed, much of our focus at OLAM, the network of 69 Jewish and Israeli international development organizations that I head, has been striving with our partners to root out the culture of saviorism from our work and assume a humbler posture.

Yet, despite some of her implicit bias, Meir was deeply committed to the flourishing of other developing countries. For her, much of this work was lishma—valuable in and of itself. MASHAV was spurred in part by geopolitical and economic considerations and rooted in an aspirational vision of the role of Israel and the Jewish people in the world. It was the right thing to do morally, even if it proved not to be the most effective thing strategically. Despite the diplomatic fiasco of 1973, Meir said that she was prouder of Israel’s development work than of any other program she oversaw in her entire political career.

A Story that Bears Repeating

I believe that we should continue to tell the story of Israel’s early investments in international development, in all its complexity.

For one thing, elements of this story are deeply inspiring. Despite facing a very real fiscal deficit, Israel’s early leaders did not adopt a scarcity mindset when it came to the state’s place in the world of nations. They were able to look beyond their own concerns and see others facing similar challenges. In response to one of the biggest global issues of the 20th century (and today)—the vast inequities between low-income and high-income countries—the fledgling state of Israel not only pitched in but excelled.

Embedded within this story are several important lessons for today’s Jewish leaders grappling with questions of how to best address competing needs, such as local versus global and Jewish versus general. The story of MASHAV’s launch demonstrates that even in a case of limited resources, scarcity does not preclude generosity. It is possible to devise “both/and” models that meet internal needs with an eye simultaneously turned towards helping others. Self-interest and moral convictions can go side by side. Short-term setbacks need not determine a program’s long-term worth, especially when the program is an expression of one’s deepest values.

This story is also an important reminder that Israel can do much better today. The Israeli economy has grown significantly since its early days. Having crossed the threshold from developing country to developed country a while ago, Israel now sits in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), a forum of the 38 wealthiest countries in the world. While Israel no longer faces the dire economic situation that initially motivated its international development program, the imperative to do this work remains, and it finally has the wherewithal to make a significant financial contribution to global development. Yet, Israel consistently ranks lowest among those nations in terms of its assistance to developing countries. MASHAV, once the largest department in Israel’s Foreign Ministry, now operates on a shoestring budget. I have heard Israeli civil servants say they are embarrassed to show up in international forums because Israel’s investment in international development is so low. This is a far cry from Israel’s focus on this work in its early years.

This fact may come as a surprise to those who are familiar with Israel’s humanitarian aid and international development work only from the headlines. What many people don’t realize is that most Israelis working in these fields nowadays are employed by NGOs, non-profit entities that don’t receive funding from the Israeli government. Many do exemplary work using the highest professional and ethical standards, yet the total budget of all Israeli non-profit organizations working in developing countries is less than the annual budget of HIAS, an American Jewish immigrant aid organization that partners with OLAM.

Historical stories are important because they shape who we are, how we see others, and how we make meaning of the world. Inside Israel, many have forgotten the story of Israel’s early investments in international development. In the current Israeli political climate, which defines Jewish values in the narrowest possible sense and is increasingly xenophobic, it’s important that Israelis share stories like these, that amplify the universal dimension within Zionist thought and ground such universalism in Jewish values and historical experience.

Outside Israel, there’s a tendency to see the country through the lens of a single story. That story varies depending on one’s politics and predilections: an embattled Israel surrounded by foes, Israel’s ongoing military occupation of the Palestinians, Start-Up Nation, you name it. The danger of a single story, however, is that it flattens complex realities into something unidimensional.

As a sovereign state, Israel cannot be reduced to its domestic policies alone, no matter how significant those policies are. Foreign policy is an inherent part of sovereignty. For the world’s wealthiest countries—among which Israel now numbers—there’s also an expectation to contribute to the global good. Political theorists talk about foreign policy in terms of the “3 Ds”: defense, diplomacy, and development. Anyone who cares about having the Jewish state show up as its best self in the world must care about this part of the story as well.

With the birth of the modern State of Israel 75 years ago, the Jewish people attained unprecedented power. For those who accept the notion of power as a corrupting force, Israel is deeply suspect, and thus runs contrary to the idea of tikkun olam. But what if power is an opportunity, not just a problem? What would it look like to use the tools of statecraft—an army, a legislature, a diplomatic corps—to be a force for good in the world and, to borrow a phrase from Golda Meir, to serve as “a continuation of our own most valued traditions and an expression of our own deepest historic instincts”? What if the role of tikkun olam is not only to speak truth to power, but to leverage it?

These are some of the most important questions of our time. It is because they lack easy answers that they deserve serious attention and exploration alongside other major questions impacting Israel and the Jewish people.

So, how do you say tikkun olam in Hebrew? Loud and clear, and with the conviction that this is an important part of Israel’s story, crucial for understanding the past and for imagining the future.

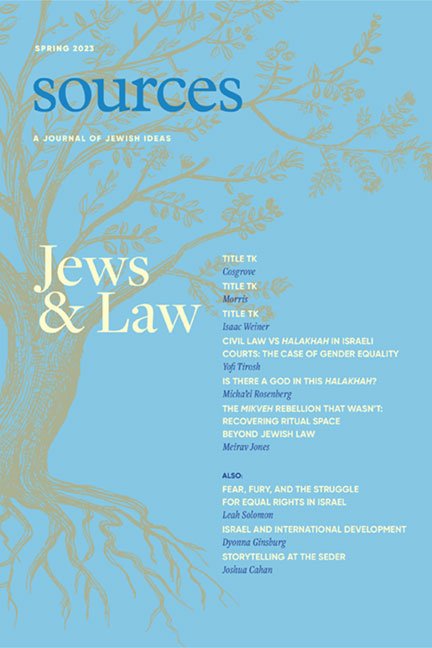

This article appears in Sources, Spring 2023.