Fear, Fury, and the Struggle for Equal Rights in Israel

PRESCRIPTIONLeah Solomon

Leah Solomon is Chief Education Officer at Encounter.

I feel profoundly privileged to be able to make my life in Israel.

For centuries, our existence as Jews was defined in large part by our powerlessness, resulting in tremendous devastation. Part of what motivated me to build my life here is my perception of Israel as the most important project of the Jewish people in the past 2000 years. I feel invested here in a way I never did in America. While I'm embarrassed to admit that I never voted in the six years I lived there as a legal adult, there's a reason I haven't missed a single election since moving here 24 years ago: the fact that we now have the sovereign power to determine our people’s present and future brings with it both unprecedented responsibility and extraordinary opportunity.

Yet despite my deep sense of belonging and commitment to this country's future, ever since the recent elections, I’ve felt mostly numb.

I’ve been participating nevertheless in what feels like a civic duty, joining thousands of my fellow Jewish Jerusalemites outside the President’s house for weekly demonstrations against the governing coalition’s proposed judicial restructuring. But as the crowd around me has throbbed with thousands of people ostensibly united in a shared objective, I’ve felt disconnected from the impassioned slogan-chanting, flag-waving, and political oratory. It’s discomfiting to feel detached in the face of what so many Israelis see as the most ominous existential threat in Israel’s history.

It's clear to me that just beneath my numbness lies deep heartache and pain: at such a consequential political juncture, and even as the northern West Bank has exploded with violence in recent weeks, millions of inhabitants of this land—many of whom are my dear colleagues and friends—are completely invisible, not only to the government but to most of those protesting in the name of democracy from across religious and political spectra. Their suffering is invisible, their rights are invisible, and, on a deep level, their very humanity is invisible.

In this land that is home to two peoples of nearly equal number, and though the main slogan promoted by protest organizers in Jerusalem is “Protecting our Shared Home,” the current protests are focused almost exclusively on the impact of proposed governmental actions internally within Israeli society. The speeches, the signs, and the messages protest leaders disseminate to the media call for democracy, equality, and the protection of minorities—specifically for Israeli citizens. The millions of stateless Palestinians who live in territories under Israeli control without the very rights we chant to protect, and the question of whether and how these values should be comprehensively manifested for all inhabitants of this land, are for the most part absent from view and left unspoken.

When I manage to get past my frustration that the suffering and pain of so many people and communities I care about are invisible to my fellow Jewish citizens, I recognize that this gaping hole in their field of vision is rooted in a mindset and national ethos that is driven, at its core, by fear.

******

Fear and trauma permeate our lives as Jews in this land.

I felt it most intensely during the 2014 Gaza War. I remember the panic I felt when the first rocket siren went off in Jerusalem. It was late at night, long after my young children had settled into deep, heavy sleep. My husband and I were only two people, but we carried all three sleeping children from their beds to the reinforced safe room, downstairs and at the opposite end of our apartment from their bedroom, within the minute-and-a-half the siren gave us before the Hamas-fired rocket’s potential impact.

Moments later, in the safe room, our children now lying—somehow still asleep—on the cold tile floor and my heart throbbing in my ears as we heard the boom of the Iron Dome interception, I felt an acute responsibility to protect these innocent beings whom I, as an immigrant, had actively chosen to subject to this reality. In that moment, nothing else mattered to me but their safety.

The fear was most potent that summer, but the broader experience of fear—along with the ways I’ve tried in vain to shield myself and my family from threats that trigger it—is deeply familiar from many other moments both before and after: avoiding buses and cafes during the Second Intifada; crossing the street when I heard teenagers speaking Arabic during the “knife intifada” of 2015-16; making sure I was always closest to the street when walking my children to preschool in the weeks after an alleged car-ramming attack in Jerusalem in late 2014 so that in case of another such attack, I might succeed in protecting their tiny bodies with my own. In periods of heightened violence, it is a near-constant effort to somehow outmaneuver the randomness of terror.

My fear reared up again most recently this past November, when there was a bombing at a Jerusalem bus stop precisely when all three of my children were riding buses on their way to school. Even now, I need only conjure the image briefly, and the panic I felt until I knew they were safe immediately floods my body.

The fury of Palestinians at the immeasurable harm we have caused them is not unjustified, and simultaneously, our fear as Jews is not unfounded. Our two peoples have inflicted tremendous pain on each other over the past century, costing tens of thousands of lives. Our fear is real and visceral and rooted both in events that we ourselves or our loved ones have experienced, as well as in the inherited trauma born of generations of persecution.

Every Israeli Jew has their own version of this fear. We carry it with us at all times, ready to be called up at a moment’s notice.

And while in my experience it arises most forcefully for most of us in anticipation of acts of terror, many Israeli and American Jews hold a more generalized version of this fear: the fear that if Palestinians in this land ever became the majority and were granted the rights we Jews see as inalienable for ourselves—especially the right to vote for the only sovereign government in this land—they would vote Israel out of existence. So many of us take for granted that their hatred for us is so great that this assumption can go unchallenged.

******

Many Palestinians living in this land are acutely aware of Jewish fear. In some ways, they know the consequences of our fear—the actions that our government and army take to mitigate the threats we view Palestinians as posing—better than we know them ourselves: they bear them on their bodies every day of their lives.

I recently heard my colleague, Palestinian peace activist Sami Awad, speak about the first time he truly began to understand Jewish fear, during his participation in a Palestinian delegation to visit Auschwitz: “As I stood there taking in the enormity of the horror wreaked on the Jewish people during the Shoah,” he told our group of Israeli Jews, “I heard an Israeli teacher speaking to her students, who were visiting the death camps in Poland as part of their high school curriculum. ‘If we’re not vigilant,’ she said, ‘another Holocaust could happen to us today, in our own land.’”

Sami then said, “And you know who the teacher was speaking about, right? As I listened, I realized she was talking about me, about my family and friends and all Palestinians. I know the Passover liturgy teaches that in every generation another enemy rises up to destroy the Jewish people. I suddenly understood that that’s who we are in her eyes and that’s how she’s teaching her students to see us: as the enemy who seeks to destroy them.”

Another Palestinian colleague put it more simply: “When I approach a checkpoint,” he shared, “I’m not afraid of the soldiers; I’m afraid of their fear.”

Palestinians are painfully aware, too, of our more generalized existential fear. My friend Ghada, who is one of the almost 40 percent Palestinian residents of Jerusalem, once asked me, “Do you know what it's like to be seen in your own city solely as a ‘demographic threat’?”

When our fear is activated, as it has been recently with the sharp rise in violence, it’s exhausting and debilitating. But even when it’s latent, during the regular months- or years-long intervals between waves of terror, fear nevertheless has a habit of quietly suffusing everything we do, ready to surface the moment we perceive the crushingly familiar threat of an attack or contemplate a future in which Palestinians comprise more than 50 percent of inhabitants between the river and the sea.

And like me in our safe room with my blissfully oblivious sleeping children, like the Israeli teacher Sami encountered in Auschwitz, and like the soldiers Palestinians meet at checkpoints or the Jerusalemites who wonder warily how many children Ghada has—when we are overwhelmed by fear, we will do anything we believe is needed to protect ourselves and those we love.

******

There is a psychological phenomenon that my colleague Yona Shem-Tov teaches about in this context, known as “inattentional blindness”—a state in which we fail to notice stimuli within our field of vision, because our attention has been narrowly directed toward specific other stimuli.1 In an experiment demonstrating this phenomenon, observers tasked with keeping track of the number of passes between members of each team playing a basketball game failed to see a person dressed as a gorilla walking through the middle of the court.

While this example is benign and even mildly amusing, others demonstrate how inattentional blindness can be dangerous and even life-threatening. In a more relevant example for our purposes, a driver hears a police siren behind her, causing her to focus all her attention on the speedometer. Her focus on how fast she is driving mitigates the real, if minor, threat of receiving a ticket, but her inattentional blindness prevents her from seeing greater threats such as a pedestrian crossing in front of her car or another vehicle merging into her lane.

Fear can protect us, but it also limits us. It can cause us to focus narrowly on specific threats that lie within our field of perception while hindering our ability to perceive other, perhaps greater threats, that lie in plain view but outside the boundaries our attention has defined for us.

******

The current struggle in Israel can be broadly understood as two camps competing over different visions for Israel’s future. While many in both camps tend to assert that Israel should be both Jewish and democratic, the “Jewish camp”—the governing coalition and their supporters—is occupied primarily with further entrenching their vision for the Jewish nature of the state, while the “democracy camp”—the opposition parties and those protesting in the streets—is more focused on bolstering democratic values and institutions.

I believe these two approaches embody two different paradigms for how both Israeli and American Jews integrate into our worldview the millions of stateless Palestinians living in this land: the “ideological paradigm” and the “fear paradigm.”

The ideological paradigm, reflected in approaches such as the Otzma Yehudit party platform and the Nation State Law, asserts an exclusive Jewish right to self-determination in the entire land. This approach puts forward a vision in which not only do Jews have a right to live in security in our historic homeland, but the aspiration for Jewish control over Greater Israel supersedes all other considerations, and the Israeli government bears little to no responsibility for the rights or well-being of non-Jewish residents.

Love Jewish Ideas?

Subscribe to the print edition of Sources today.

Those who embrace the fear paradigm, on the other hand, affirm in principle that stateless Palestinians deserve to have their rights actualized, but are simultaneously driven by a pervasive and enduring fear to assert resignedly that for now and for the foreseeable future, the obligation to implement rights for Palestinians is outweighed by the need to protect Jewish security, which they believe would be threatened by actualizing those rights.

The classic two-state solution, which many Israeli and American liberal Zionists still view as the optimal outcome, is rooted deeply in the ethos of the fear paradigm. In focusing on separation between Israelis and Palestinians, its primary objectives from an Israeli Jewish perspective are to minimize the likelihood of terror attacks and to avoid the demographic threat of a future Palestinian majority voting Israel out of existence. Though touted as a peace plan, the two-state model thus perpetuates the framing of Palestinians in relation to Israel primarily as a threat, or at best an unwanted burden, by assuming that even in a future two-state reality Palestinians will continue collectively to seek Israel’s destruction, and that the only way to ensure Israel’s security is through military deterrence rather than the building of healthy relations that would render military deterrence unnecessary. In my experience, the way most Jews understand the two-state model entails no proactive vision for a peaceful and flourishing shared future for Jews and Palestinians.

Given that the physical interspersion of Palestinian and Jewish communities throughout the West Bank and East Jerusalem today makes the possibility of dividing the land into two contiguous states less viable than ever, clinging to this outdated model as the desired outcome for a far-off future serves primarily as a way to reassure ourselves that we genuinely believe in democracy for all, while abdicating responsibility in the present for grappling with the crushing reality for millions of stateless residents under Israeli control.

I’m troubled too by how growing up steeped in the fear paradigm shapes the minds and hearts of our children. It is hard to accept cognitive dissonance, and natural to seek moral consistency. It should not surprise us that a generation raised to believe that a thriving Jewish future is regrettably dependent on a lack of rights for Palestinians would slide gradually into the ideological paradigm, coming to see Palestinians as fundamentally undeserving of rights. The steep rise in votes for far-right Israeli parties in the most recent election, especially among young Israelis, seems to illustrate this disturbing shift.

And while our attention has been focused for decades on minimizing the threats we perceive from Palestinians, many who identify with the “democracy camp” have lost sight of the fact that there is no such thing as democracy for some. Once we’ve normalized the idea that it is acceptable to deny fundamental rights to some, it becomes all too easy to accept the erosion of rights for others. As Martin Luther King, Jr. wrote in his letter from Birmingham jail in 1963, “Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere. We are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny. Whatever affects one directly affects all indirectly.”

Our collective inattentional blindness has prevented us from internalizing that our destinies are inextricably linked and that our failure to ensure a better reality for Palestinians is therefore harmful not only to them but to us as well.

******

Those of us who care about Israel and about the ability of Jews to live safely in this land need a new paradigm driven not by ideology or fear, but instead by a proactive and courageous Jewish vision for a shared future which recognizes that all inhabitants of this land are here to stay and that it is in the interest of all of us to ensure rights for all.

We need to free ourselves from seeing Palestinians solely as a threat and begin developing the muscle of relating to them in their full humanity.

This does not mean ignoring true threats to security. There are those who aim to cause injury and death, and Israel has a moral obligation to protect everyone under its authority, including acting to prevent attacks while minimizing collateral impact on uninvolved bystanders to the highest degree possible. We need to be able to trust that our leaders will keep all of us safe, a goal which the composition of the new government has made far more challenging.

At the same time we must recognize that not all our fears are warranted and not everything we dread will come to pass. While individuals can and do cause substantial harm, Palestinians as a group do not pose an existential threat to Israel; and even if Palestinians as a collective wished to wipe us out, they lack the power to do so. The vast majority simply want to live their lives in full dignity and equality.

More importantly, reality-as-it-is is not reality-as-it-must-be. We must never assume that just because many Palestinians bear tremendous animosity toward Israel in the current reality, the same would be true in a transformed future. No human being is born to hate. I draw hope from how rarely Palestinian citizens of Israel have committed violent acts against Jews over seven decades of living together, despite ongoing racism and governmental discrimination against them; changing the reality on the ground can help shape a different path forward.

Focusing on a new paradigm for a shared future also doesn't mean procrastinating on reforming Israel's policies toward Palestinians. In the absence of an imminent long-term diplomatic agreement, we must do everything possible to reduce the massive and sustained suffering that Israel's policies inflict daily on millions of Palestinians. Particularly given that the current Israeli government has outlined a policy agenda that will make life more difficult for Palestinians—for example, by increasing the number of home demolitions, eviction orders, and building of Jewish communities in the West Bank including on private Palestinian land—Jews who care about Israel have an even greater responsibility to support civil society initiatives to ease the daily lives of Palestinians living under Israeli control.

Finally, in the long term, Israelis and Palestinians must map out a diplomatic agreement that will ensure security, equality, dignity, justice, and freedom for all. We will need to determine together whether this can be best accomplished through two states, or one, or an arrangement such as a confederation or federation. But at this point we are nowhere near ready for a debate about what shape a final diplomatic agreement should take. Too often conversations that jump directly to discussing the optimal “solution” hit a dead end, as people quickly conclude that there is no feasible solution and that the ever-evolving status quo is the only option, irrespective of how destructive it may be.

What we desperately need, in the space between the short-term objectives of ensuring security and minimizing harm and the long-term goal of a diplomatic agreement, is a robust Jewish exploration of our highest aspirations that takes as its starting point that our two peoples' stories are interdependent and intertwined and that we must shape a new path toward living in this place together.

We have for so long focused on what we stand to lose by living with Palestinians, that we have never taken the time to ask what we might gain.

And there is so much to gain. I am grateful that, through my work, I regularly encounter Palestinians and Israelis of extraordinary compassion, courage, and determination to strive for a better future for all inhabitants of this land. Our peoples abound with potential for good.

Our task now is to seed a sea change in Jewish communal discourse, culture, and priorities toward integrating a commitment to Palestinian well-being into our existing commitments to Israel and its future. All those who care about Israel and the Jewish people should vocally reject narratives which position Jews and Palestinians collectively as adversaries in a zero-sum game and reframe engagement with Israel toward a widespread recognition that the ability of each people to thrive depends on the other thriving as well.

This means first and foremost shifting Jewish education to align with this goal. American and Israeli Jews alike must teach our children and ourselves to encounter Palestinians in their full diversity, complexity, and humanity. Jewish educators should include Palestinian stories, perspectives, and lived experiences as part of Israel education. This means ensuring Palestinian communities are visible on maps, teaching Palestinian literature and history, and meeting and hearing from Palestinians.

We should likewise shift philanthropic and economic investment toward ensuring the security, dignity, and rights of both Israelis and Palestinians. We should support and advocate for legislation such as the Nita M. Lowey Middle East Partnership for Peace Act, which seeks to build foundations for future reconciliation and coexistence. Particularly given the nature and priorities of the current Israeli government, American Jews should double down on support for diplomatic efforts to advance a future in which both Israeli Jews and Palestinians will live in security and with full rights.

In such a scary and dark moment in Israel, it may seem naive or even delusional to wax eloquent about a transformed Israeli-Palestinian reality. I believe it is precisely the opposite: any conversation about the future of Israel—our democracy, our governmental institutions, our foundational values—cannot be separated from the reality of two vibrant and resilient peoples living permanently throughout this land, and any effort to separate them is doomed to fail. Only by seeing and grappling with the full picture will we be able to envision and build a better future.

******

My colleague Mahmoud recently shared his belief that to achieve liberation, Palestinians will first need to help liberate Jews from our own fear and trauma. I would be grateful to any Palestinian who supports that process, but the ultimate responsibility for this work is our own. Now is the time for us as a people to move beyond the paralysis of fear, so that we can not only liberate Palestinians, but also work together to develop a positive vision for our existence in this land—a vision in which all inhabitants live with security, equality, dignity, justice, and freedom.

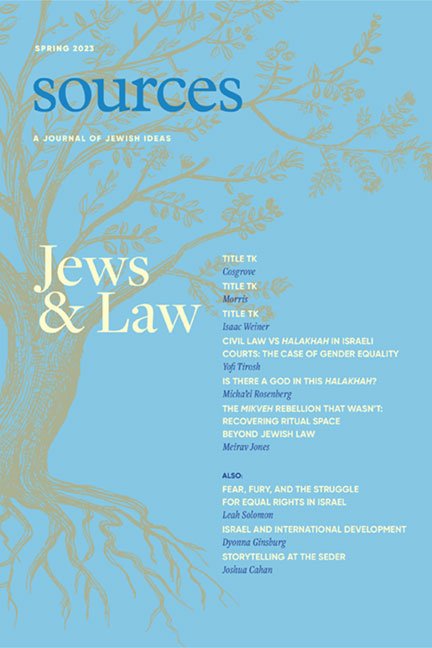

This article appears in Sources, Spring 2023.

Endnotes

1 Arien Marck and Irvin Rock, Inattentional Blindness (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2000).