A Choosing People

JEWS AND LAWElliot Cosgrove

Elliot Cosgrove is the rabbi of Park Avenue Synagogue, Manhattan.

Few and far between are the occasions when I, a congregational rabbi affiliated with the Conservative movement, receive a question concerning Jewish law, halakhah. As Passover approaches, a congregant or two may inquire about the kashrut of a new food product on the market. End of life, with its concomitant questions surrounding medical directives, burial, and then shiva, invariably elicit questions regarding Jewish law. So too, on joyous life cycle occasions like weddings and circumcisions, I am asked to weigh in on halakhic matters for my congregants. I vividly recall one woman facing the prospect of terminating her pregnancy, asking me for Judaism’s view of when life begins. This list is not a long one, and the very fact that I can name these instances is proof of their rarity: they are the exceptions that prove the rule. The Jews I serve are not halakhic Jews living lives bound by Jewish law.

Non-halakhic as my Jews may be, their lives are nevertheless filled with mitzvot. Here, I am referring to mitzvah neither as a “good deed” like volunteering for a local food-pantry, nor according to its literal meaning of “commandment.” Instead, I am defining mitzvah as a positive act of Jewish identification. Whether my Jews light Shabbat or Chanukah candles because they feel commanded by God to do these particular acts, or because doing so triggers a warm wave of nostalgia and spiritual sentiment, I do not know; I just know that many do, and they feel that doing so makes them more Jewish.

Mitzvot and the aspiration to perform them abound in the souls of American Jews. The decision to order from one side of the menu but not the other, the decision to purchase tefillin for their children as they reach bnai mitzvah age, the decision to study Torah or participate in communal prayer—the subset of American Jewry I serve, in their own inchoate way, often perform and continue to aspire to perform mitzvot. For many (but not all) of the Jews I serve, the non-performance of mitzvot is not so much a “no,” as it is a “not yet.” Even if they are not observing mitzvot, they feel they should, they could, and might one day do so. Moreover, nearly twenty-five years into my rabbinate, I believe that my congregants hold the expectation that as their rabbi, I will urge them to do so.

This is the lived life of an American rabbi: leading Jews who live non-halakhic lives, but who, nevertheless, aspire towards halakhic moments. Jews for whom Jewish practice is episodic, opportunistic, and located predominantly in life’s poetic moments: birth, death, festivals. Jews who live comfortably with the gap between their personal practice and the standard practiced and preached by their clergy. Jews who hold idiosyncratic (and, to my mind, sometimes amusing) spheres of halakhic concern, like the congregant who berates the cantor for skipping a stanza of the Geshem prayer for winter rain before leaving for his post-shul round of golf. Jews who perform and aspire to perform mitzvot, but only insofar as such observances do not impinge on their secular commitments— their theater tickets on Saturday afternoons, their children’s club sports on Saturday mornings or, an expectation that they observe the dietary laws of Passover beyond the Seder itself.

In short, their mitzvot are volitional lifestyle choices, not commanded deeds existing within the totality of a halakhic system. And while my observations are those of a Conservative rabbi, I would contend that the difference between Reform, Conservative, and Modern Orthodox Jews is a difference of degree and not of kind. Everyone is picking and choosing mitzvot. No longer a prix-fixe menu, Judaism has become a buffet prepared to serve the individual tastes of the contemporary Jew.

Long past are the days of “na’aseh v’nishma,” of the Jewish people standing at the base of Mount Sinai, declaring, “We will do, and we will listen,” accepting the law sight unseen and in its totality. For two thousand years, it was mitzvot, systematically structured in the form of halakhah, that provided not only the means by which Jews could perform the will of God, but also the scaffolding for Jewish communal practice by which Jewish identity and covenantal fidelity could be transmitted from one generation to the next. As we read in Genesis, “Abraham circumcised his son Isaac when he was eight days old as God had commanded [tsiva] him.” (Genesis 21:4). For Abraham, for the Israelites at Mount Sinai, for Jews throughout history, praxis was the means to apprehend, revere, fear, and follow God’s will. Not discrete mitzvot but mitzvot located within an all-encompassing system, with the routine and habitual nature of halakhah as its very point. When we lie down and when we rise up, when we eat, shave, and defecate—and most of all, when we want to follow halakhah and when we don’t. It is a sense of duty, not discretion, that impels a life of mitzvot, a sentiment embodied in the Talmudic dictum: “Greater is the person who performs because they have been commanded than one who performs without being commanded” (bKiddushin 31a). As Yeshayahu Leibowitz argued in his 1953 lecture on “Religious Praxis: The Meaning of Halakhah,” no matter the circumstance in which Jews found themselves, in heeding the encyclopedic halakhic codes of Maimonides, Joseph Karo, and others, they were assured of living in covenantal accordance with the will of God.

Divine will aside, halakhic observance also had a profound sociological function in pre-modern Jewish communities, in that it served as the bonding agent for a dispersed people. No matter where or when Jews lived, they were assured a common practice with their fellow Jews. As Solomon Schechter wrote:

What connection is there…between Rabbi Moses ben Maimon of Cordova (known as Maimonides) and Solomon ben Isaac of Troyes (known as Rashi)…? One lived under a Mohammedan government; the other under a Christian government…The one spoke Arabic; the other French…The one was a thorough Aristotelian and possessed of all the culture of his day; the other was an exclusively rabbinic scholar and hardly knew the name of Aristotle… But as they both observed the same fasts and feasts; as they both revered the same sacred symbols, though they put different interpretations on them…in one word, as they studied the Torah and lived in accordance with its laws…the bonds of unity were strong enough even to survive the misunderstandings of their respective followers.

In the context of a halakhic system, mitzvot were the sacred shibboleths by which Jews established and sustained conscious community. I am under no illusions that pre-modern Jews living in the context of Hellenism, Iberian Sepharad, or early Ashkenaz lived punctiliously observant lives or, for that matter, uniformly believed that the Torah was actually given at Mount Sinai. Such halcyon myths of yesteryear say more about us today than they do about the actual lives of a millennia of Jews—they inspire the nostalgic impulse that motivates some Jews today as they fulfill the mitzvot they find meaningful. It was, however, because Jews lived in self-governed communities distinct from the non-Jewish communities of their respective host countries that the assumption and authority of the halakhic system could be both preserved and enforced. The threat of excommunication from within and the inhospitable nature of host communities from without ensured the normative status of halakhic observance. To be Jewish was an all-embracing and unquestioned identity that, antisemitism permitting, was generationally assured.

The arrival of the Enlightenment and emancipation would forever change European Jewry’s relationship to religious truth, and by extension, halakhah. Be it Spinoza’s challenge to scriptural authority or Kant’s cri de coeur to “dare to know,” it was the tools of reason, not divine revelation, by which post-Enlightenment Jews engaged with reality as construed by the modern ethos. Humans, no longer born into this world with a host of obligations to God, were instead born with a series of God-given and inalienable rights. Not only had the Torah been dethroned as the first and ultimate source of truth, its legislative authority over the lives of Jews was diminished. Hitherto understood as a means by which Jews could express their freedom by way of service to God, halakhah was now increasingly viewed as an impediment to their very freedom.

The modern conception of individual, autonomous freedom enabled Jews to breach the boundaries of their insular communities, thus rendering the rabbinic community’s ability to enforce Jewish practice symbolic at best. For all its gains, in transforming Judaism into a voluntary and individualistic enterprise, the one-two punch of the Enlightenment and civic emancipation had a cascade effect on Jewish life, its greatest casualty being the authoritative claims of halakhah. The historic and metaphysical link between Jew and God, and between Jew and Jew, were irreparably severed.

The last two centuries of Jewish life may be understood as a taxonomy of responses to the Enlightenment and emancipation, at least within the Ashkenazi experience. Leaving aside those who opted out of Judaism entirely, the three inaugural denominations (Reform, Conservative, Orthodox) emerged in the early to mid-1800s as a series of efforts to sustain Judaism in the face of the counterclaims of modernity. Classical Reform Judaism made explicit its belief that observance of Mosaic and Rabbinical laws is more “apt to obstruct than to further modern spiritual elevation.” Ultra-Orthodoxy emerged in response to Reform, as an effort to defend traditional observance, perhaps best exemplified by the Hatam Sofer’s telling phrase, “chadash asur min hatorah,” meaning, “that which is new is prohibited by the Torah.”

The Conservative movement typified the “yes, and” spirit of the day, positioning itself as a halakhic movement capable of balancing tradition and change, in the words of its ideological founder, Zechariah Frankel, “maintaining the integrity of Judaism simultaneously with progress, that is the essential problem of the present.” Modern Orthodoxy’s Samson Raphael Hirsch was not the first to provide taamei hamitzvot (reasons for the commandments), but the fact that he did so systematically in his monumental book, Horeb, was also indicative of the zeitgeist. Moral, ethical, communal, spiritual, and aesthetic justifications for halakhic observance are all answers to the post-Enlightenment question of why Jews should live in accordance with Jewish law if they are not commanded to do so.

Most pointedly, in the early 20th century, the founding ideologue of Reconstructionist Judaism, Mordecai Kaplan, reframed all of Judaism from a halakhic system of commanded mitzvot to a religious civilization of chosen folkways. After all, in a voluntaristic society where religious observance is no longer obligatory, Jewish law cannot actually be law.

Love Jewish Ideas?

Subscribe to the print edition of Sources today.

Each one of these thinkers (and the movements they represented) share the same defensive posture in response to the overarching question: How do we maintain Judaism in the face of modernity’s challenges?

And while the thinkers thought and the movements moved, the Jews in the pews made their own choices. Most immediately, the scope of Jewish law became increasingly circumscribed. Once an all-encompassing civil code by which a community functioned, halakhic observance was now delimited to matters of personal status (marriage, divorce, etc.) and select religious ritual and practice. For some, Judaism continued to inform matters of ritual purity, dietary practice, and daily behavior. For others, Judaism now informed only those spheres of Jewish living into which a person self-selected, Passover Seder, Chanukah candles, circumcision, and the like.

Some Jews sought to align their personal Jewish practice with the Jewish community in which they affiliated. Other Jews sought to update and adapt halakhah to conform with and accommodate their new sensibilities. Far more Jews found themselves living comfortably with the dissonance between their personal patterns of observance and what was preached from the pulpit. At best, mitzvot came to be viewed as a series of occasions when Jews could positively identify with their Jewish past, present, and future. At worst, Judaism became a spiritual practice no better or worse than the latest self-help book.

This is the state of affairs in which we find ourselves today. The decisions of Jews to observe or not observe mitzvot are made by way of personal choice and communal affiliation, some still in compliance with a halakhic system understood to represent the will of God, but the majority independent of such considerations. God’s presence, once the means for Jews to understand themselves as living in accordance with the Divine will, has retreated to the shadows. This bond, once the scaffolding by which Jews throughout the world could transcend differences of geography, culture, and intellectual inclinations by way of shared religious practice, is tattered. The commitments American Jews have towards halakhah reflect their relationship to their Judaism as a whole: episodic, voluntary, and more often than not, a matter of mere nostalgia.

Sober as such observations may be, they serve to clarify the task ahead. Rabbi Yitz Greenberg once famously quipped, “It doesn’t matter what denomination you belong to—as long as you are ashamed of it.” Whatever my opinions regarding the rest of the Jewish world in its engagement with non-halakhic Jewry, good conscience demands that I begin by turning the mirror toward myself and my lifelong denominational home.

For all the efforts of the Conservative movement to fortify American Jewry by maintaining Judaism “simultaneously with progress,” its shrinking share of devotees (as evidenced by the latest Pew studies) provides ample reason for a tactical reappraisal. As the movement’s Committee on Jewish Law and Standards has expended its energy debating the terms and pace of halakhic development—e.g., is electricity on Shabbat permissible or not in the 1950s; can women be counted in the minyan in the 1970s; can LGBTQ Jews serve as clergy in this century—the lived lives of Jews have been overlooked. The vast majority of contemporary Jews are neither strict nor loose constructionists in their interpretive approach to halakhah; they are not halakhic at all. Non-halakhic Jewry has voted with its feet, making our movement a caricature of the adage, “a leader without followers is just taking a walk.”

The rise of Chabad and the Lubavitch movement’s deployment of emissaries (sheluchim) and mitzvah campaigns (together with a formidable online presence) provides a useful counterpoint. In emphasizing the performance of individual mitzvot but not “halakhic observance” writ large, Chabad recognizes both the spiritual aspirations and the practical limitations of the contemporary Jew. In contradistinction to the Conservative movement, Chabad has positioned itself as the non-judgmental voice of authentic Judaism, evincing no interest in updating halakhic practice to accommodate present day sensibilities on matters of gender, sexual orientation, or otherwise. One redemptive mitzvah at a time, retrieving the spark embedded deep within every Jew. Chabad and Conservative Judaism begin from the same working premise, the gap between the assimilated Jew and halakhic observance. The difference—that has made all the difference—is the tactical response to this gap.

Ultimately, though, neither Chabad nor the Conservative movement, nor for that matter, any movement, is in possession of the sole answer. Furthermore, denominational labels are not as significant as they once were. There is more than enough work to go around, and while our ideologies, practices, and tactics may differ, we would do well to remember that we stand united in our unyielding mission to secure the future of Judaism. The task of religious leadership must be to facilitate the modern individual’s retrieval of the Divine by way of a life of mitzvot. God’s presence may have receded, but it has not been utterly eclipsed.

The calling of the hour is to train a generation of rabbis, Jewish educators, and communal professionals with the spiritual, pedagogic, and practical skills to capture the hearts and souls of an American Jewry for whom Jewish affiliation is one of individual and voluntaristic choice. The Conservative movement should disabuse itself of the belief that its devotees are halakhic and rename its Committee on Jewish Law and Standards—the Committee on Jewish Life and Spirit, with its sole focus to inspire, educate, and empower Jews towards a life of religious observance.

All movements would do well to reorient their arguments for observance away from the thought that anyone is required to “do Jewish.” While the language of “obligation” may have run its course, “commandedness” has not. The performance of mitzvot as an expression of service to God remains a powerful driver for Jewish practice. Powerful as nostalgia may be, it does not assure the Jewish future. In the words of the late Conservative rabbi and scholar Arthur Hertzberg, “A community cannot survive on what it remembers, it will persist only because of what it affirms and believes.”

We must show Jews that the riches of Jewish practice are compelling to the spiritually searching and God-thirsting soul and can more than compete with the marketplace of secular alternatives. We must eschew an “all or none” attitude when it comes to observance and affirm every Jew’s autonomous decision to embrace a life of mitzvot, both meeting people where they are and inspiring them to live the Jewish life they seek, even if that life is not, strictly speaking, halakhic.

Rabbis are destined to serve in the time into which they are born. It serves no purpose to long for yesteryears, it solves nothing to blame our predecessors for our present state of affairs, and it is counterproductive to wag fingers at Jews for their attenuated patterns of observance or their non-observance. Having eaten of the fruit of knowledge (as cast by the Enlightenment), we cannot return to the innocence of the garden—nor do we wish to. The blessings of our present freedoms abound.

If given the choice of the challenges of my rabbinate or those of my predecessors, I would choose today over yesterday every time. I take both comfort and inspiration in the knowledge that my rabbinic vocation, different as my context may be from that of my rabbinic forbearers, is one and the same as theirs. To provide the tools and encouragement to prompt Jews to revere God, to walk in divine paths, and to serve the Lord God with all their hearts and souls. May the work of my hands, and that of every rabbi, be blessed, and may the Jewish people be strengthened through our efforts.

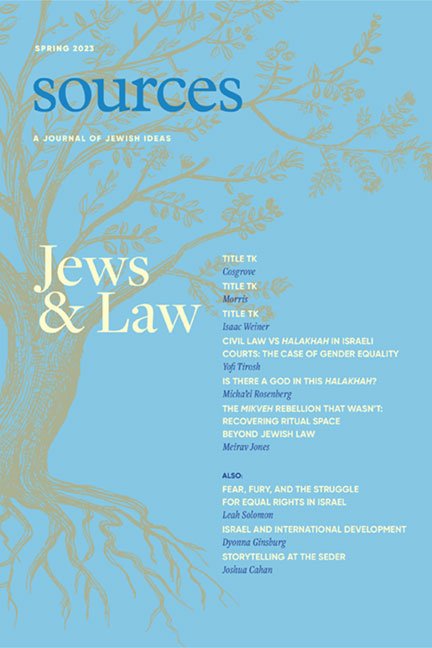

This article appears in Sources, Spring 2023.