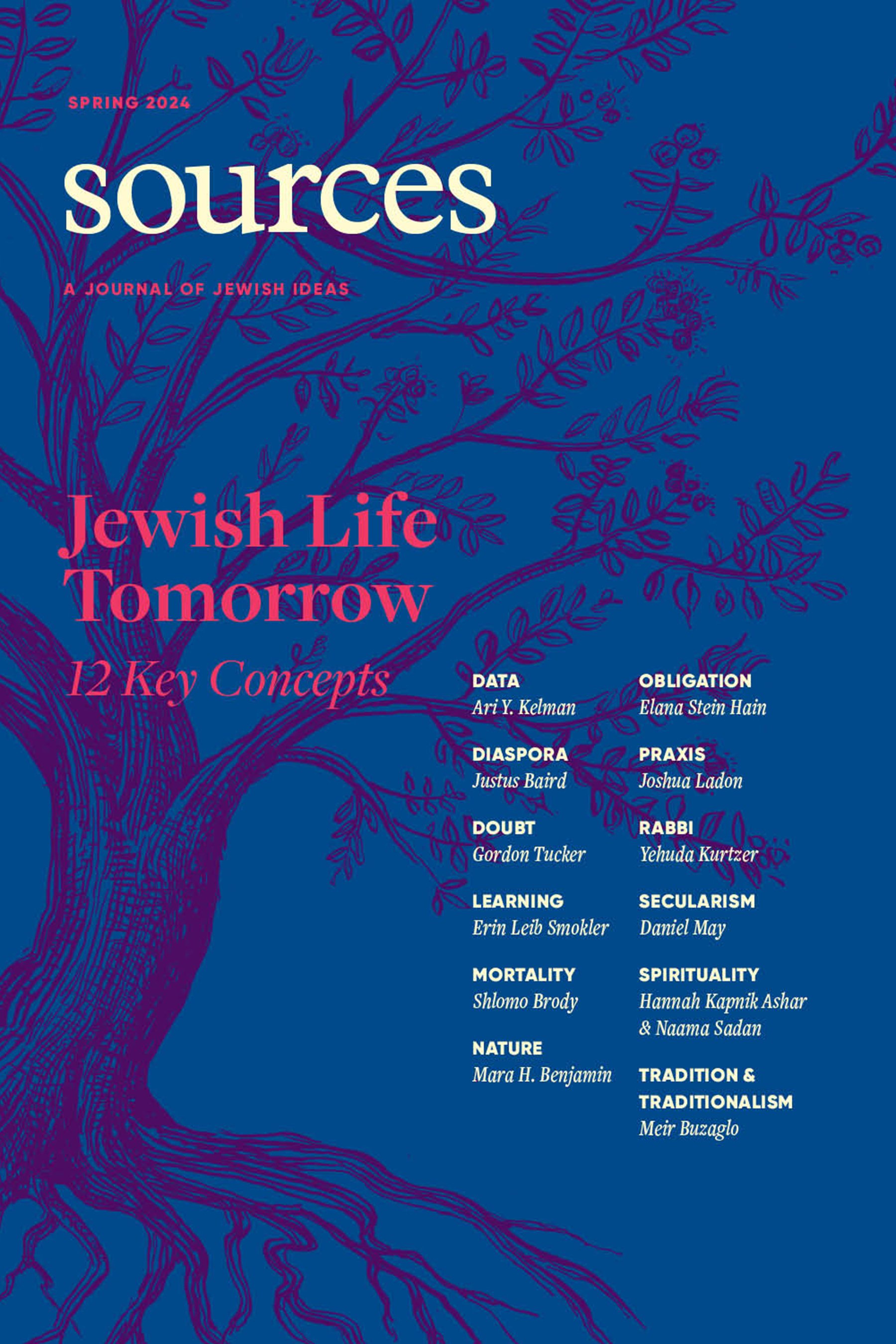

Spirituality

Naama Sadan and Hannah Kapnik Ashar

Naama Sadan is a scholar and teacher of environmental systems and Jewish spirituality. Hannah Kapnik Ashar is the founder of Rahmana, a women's prayer initiative cultivating feminine Jewish spiritual practice, and Director of Faculty with the Bronfman Fellowship.

This past July, we visited Esther Gopher, a spiritual teacher in the south of Israel, who welcomed us warmly into her home. She served us—and a stream of other learners—a hearty stew while we sat and talked about our lives. Esther then walked us through the vineyards of her moshav, drawing metaphors from the plants’ reproductive cycles to our spiritual lives, and from the female body to the idea of feminine Torah. She described feminine Torah as drawing on the capacities of a womb, which knows:

how to open,

to wait,

to hold boundaries,

to contain,

to trust that we move through cycles.

For the last 3000 years, Jewish spiritual practice has primarily been developed by men and for communities of men. The Talmud records that hasidim harishonim, “early pious ones,” would meditate before prayer; Cairo Geniza fragments reveal the hypnotic mystical poetry and incantations of Hekhalot literature; the Zohar’s most elevated and secret teachings about the nature of God are revealed through a communal process of a committed group of learners, the chevraya. The Baal Shem Tov interpreted Torah phrases to apply a holy lens to internal psychological dynamics.

Many of these sources emphasize a spiritual path of transcendence or shifting out of mundane experience; they are mental models for beginning to comprehend the Divine, images and practices toward an altered, transcendent awareness. Insights developed by people living in the bodies and social contexts of men have yielded much of the Jewish spiritual landscape that we are blessed to inherit. And for some, these keys alone will open the spiritual doors they need.

We are living in a historic spiritual moment, when a long-dormant—or at least largely unrecorded—part of the spiritual landscape is yielding new fruit: spiritual wisdom and practices that come into the world through the bodies and social experience of women. In this domain, to be spiritual is to come close to yourself and to open to the warmth of the heart. This is a spiritual world of life embedded in relationships and in ongoing encounter with our own needs and the needs of the other. It is Torah of “the spiritual, all-embracing, ordinary life” (Kauffman, 211). Feminine Torah is Torah for people with all sorts of physical bodies who are seeking to build a spiritual body that will allow them to set firm loving boundaries so that they can open at the right time.

We want to help bring this path of feminine spirituality into greater light.

NAAMA: I came to the world of Jewish feminine spirituality through my grandmother. She told our family that, at age 80, she was having a life-changing experience: learning the spiritual teachings of Yemima Avital. She said that, as a socialist and a woman who had worked her whole life for the “group,” it was hard for her to identify with an emphasis on “self-care.” She thought it was egoistic. Slowly, she said, she realized that real self-care opens something up within you. When your emotional waves calm, the essential can shine. You can sense it and follow your soul journey for your own benefit and the benefit of others. When she passed away, I signed up for a class in the Yemima Method and started practicing.

HANNAH: I first came to this feminine Torah through Naama, at a time when I was months into preparation for an exam on the legal intricacies of kashrut as part of my rabbinic studies. This Torah of the internal landscape and relationships—a kind of domesticity very different from kashrut—reminded me that Torah could be felt in my body, and could come to bear in my most intimate interactions.

NAAMA AND HANNAH: We have together had a weekly chevruta—a learning partnership—for the last three years. We learn Midrash, Kabbalah, Hasidut, and the Torah of women “rebbes” of the last 100 years. In our time together, we read, write insights, translate, sing, and weave ideas across thinkers and genres. We develop teachings and retreats. We join many others in hasidut and mindfulness: a Jewish path of wellbeing.

We invite you to walk with us through four practices of feminine Jewish spirituality. We use the term “practices” to describe the small cognitive motions and shifts we can make in service of opening our spiritual body. We chose to share these four practices because they are core to how we understand and embody this opening. These practices build on each other, moving from closed or seeking security, toward learning to open and trusting.

We start with observing: Zihuy.

We turn toward the self with warmth: Hitkarvut.

We identify what strengthens and what blocks the core: Tehum.

We support the light of our soul to enable movement from the Greater Soul: Tnu’a.

These four practices are inspired largely by practices and teachings of teacher and healer Yemima Avital, z’’l, and her students and are enriched with other teachings we have learned in our chevruta. Yemima was one of the Moroccan Jewish women who came to Israel early in its modern statehood, bringing her kabbalistic lineage along with her background in psychology and feminine wisdom. The quotations below from Yemima are our translations of her words, as taught by her students.

As we describe these four practices, you may find yourself reading this article looking for interesting ideas. We invite you instead to try walking the path in small steps: make a cup of tea and find a calm spot to sit. Pay attention to the warmth of your heart. Since Yemima taught in an exclusively oral tradition, we encourage you to read her words, or all the text, out loud as you go. You are entering a conversation, one in which insights can be revealed through the process of asking, listening, and sensing. Listen for phrases or words that resonate with you, that you want to keep with you, that might accompany you into the day.

Zihuy זיהוי: Recognizing what is essential, and what blocks and burdens

At the very core of the approach we are sharing, we want to connect to yesh יש—the essence. This is, most simply and exquisitely, existence, a creative power, God. The essence is the deepest root of our being, and it is totally good. We can recognize the yesh every time we feel joy, passion, quiet, expansiveness. Whenever something flows and just exists, it is the yesh revealing itself to us. We want to develop our attention to recognize the yesh.

And when there is an inner obstacle to our connection or growth, we want to recognize that with the same gentle attention, too. We might recognize internal barriers when feeling stuck in a loop or playing out an old script. In Yemima’s words,

Everything repeats itself like a fight with no solution.

You are in a narrow place

as if imprisoned in a tangle of imbalance.

These loops might manifest as strategies that were effective when we were children. Yemima identifies them as, “tension, anger, hesitation, doubts, closedness, and blockages,” and calls them omes עומס. For her, omes is the burden or excess we accrue, like plaque on the walls of our soul’s capillaries. In times of vulnerability, we resort to these same strategies we developed as children when we had no control—but they are no longer needed. Now we can choose, we have agency.

HANNAH: I once saw a tree in the woods that had a very misshapen part. At that spot, the bark looked mangled, worn away, and the inner layers of the tree were exposed. It looked like it was in pain. I wondered, What happened to this tree? After several minutes, I saw another tree, ten feet away, with a similarly mangled spot. But on this second tree, there was an obvious reason for the misshapen part: a fallen tree was pushing against it. Oh, I thought of the first tree, you, dear tree, are living as if a fallen tree were still against you. This is omes: responding as if the fallen tree still presses against us.

NAAMA AND HANNAH: When we find ourselves closing off or seeking acceptance and security, zihuy allows us to look and recognize: Am I responding to what’s happening in this very moment, or to something from a different time? Is this reaction in me omes?

We recognize omes, but we do not attack it, resent it, or resist it. Rather, we recognize and label, “this is omes; this is no longer essential to me.” Sometimes we can’t look at our reactions in the moment, but can later go back and look at an experience and identify: when was I responding to the present moment, and when was I responding to omes?

As with any practice, the more we recognize and distinguish between yesh and omes, the more robust our habit of recognizing will grow. This place of zihuy is not about healing old wounds. As Yemima taught, “Don’t scrounge around in the omes.” Zihuy is about recognizing that a reaction is coming from an outdated model within us. We do not strain to resolve the blockage.

Recognizing these blockages organically allows a breakthrough

however small

bringing clarity in these closed, blurred places.

Hitkarvut התקרבות: Approaching the Self, coming close to what is real in this moment

Hitkarvut is an orientation of warmth toward oneself and one’s surroundings. Instead of resisting or resenting reality, hitkarvut is a small movement toward reality. Hitkarvut is a desire to belong to what is happening, whether it is pleasant, painful, or neutral. The work here is to turn toward ourselves even when we feel that we want to turn against ourselves. It is choosing to be with ourselves rather than reject ourselves, if we can. If not, then next time.

HANNAH: One evening, in the hours before teaching a class on preparing for childbirth, I was feeling extremely irritable. I shouted at any of my children who dared to leave homework on the table or who hoped I might procure a dessert for them. I was trying to ignore the irony of acting this way just as I was about to guide a group of women into ease, presence, and depth as they approached motherhood.

But in a moment of grace, I noticed the resentment, pressure, regret, and chaos inside me. I recognized the resistance in my body, how I was fleeing from presence. I thought of a line from Yemima’s guidance for contractions during labor: “My approaching is not full of withdrawing.” I remembered how that line had struck me when I first heard it: with each contraction in my earlier childbirths, my body was approaching, but indeed my mind was turning away in fear.

That night before teaching, the feeling of chaos and rigidity I felt in my body was the same as my response to a physical contraction. I was feeling pressure—a kind of contraction—to create something beautiful, and instead of participating in that energy, I was resisting. The chaos I felt inside was an attempt to flee, to not be with the responsibility to focus. After I recognized this, my anger released. I acknowledged to my kids that I was being a petty monster, told them I loved them, and took some space.

NAAMA AND HANNAH: We turn toward ourselves by acknowledging that our value is not connected to action. Yemima taught that we were created “wrapped in a primordial layer of warmth, that isn’t conditional upon achievements or results.” We are fundamentally good and precious just because we were created, with an ancient warmth always available to us.

Unconditional warmth toward ourselves flows into the ability to welcome mistakes. Living with—and not rejecting—mistakes allows us to relax and learn. Yemima invites us to be in the ongoing flow of making mistakes and repairing:

Act according to your ability and make many errors.

Even if you do make a mistake,

You are allowed to, make mistakes and as many as you want.

Here she makes a mistake, here she repairs.

The canvas of action is broad: “act according to your ability” does not include only perfect action.

We don’t need to make an effort to be good.

A successful life is one where our heart is accepting of our mistakes,

trusts that it will find the right way from within, and repairs

and remains open

rather than clinging to security and avoiding mistakes at any price.

Our heart opens to the present experience brought to us by providence, and works with it, in the

bounds of our current capacity.

Love Jewish Ideas?

Subscribe to the print edition of Sources today.

Tehum תחום: Demarcate boundaries

In relationships, it can be tempting to approach the other by blurring the boundary between us and them. Even within ourselves, we can cross boundaries, not respecting where and when we can’t go on. Yemima describes a different model of intimacy, where we can more deeply connect with someone by being separate: “The one who listens well will experience approaching while present on her place.”

Demarcating boundaries is not a creative effort as in the English idiom “establishing boundaries,” wherein we might work to manufacture an inorganic separation. Here, we identify and label boundaries that exist at our edges, or between different parts within us (e.g., the boundary between fear and security). Each person has a natural place to stand, a place where they are at home in themselves. As we mature, we come to greater clarity about our characteristics, strengths, and purposes—the selves that inhabit our place. As we have a more robust sense of this place, our boundaries become more developed and easier to recognize.

This practice, called tehum, invokes the rabbinic concept of tehum Shabbat, which describes a boundary that defines the place where we are for Shabbat, and outside of which, we will have desecrated Shabbat by traveling. The holiness of the day is preserved by “no one [leaving] their place” (Exodus 16:29), and so, too, in Yemima’s Torah, the holiness of our connection with self and Divine is preserved when we are on our place. Tehum Shabbat is not visibly or permanently marked, but is calculated as a certain distance’s walk away from where we started Shabbat. There is an invisible radius of “our place,” and leaving the tehum means leaving that place. On Shabbat, staying within the tehum means guarding the sanctity of the day; internally, staying within the tehum means guarding the sanctity of my soul and its journey.

Tehum as a practice cultivates a very attuned clarity of one’s place, of what’s mine and what’s someone else’s; of what’s essential and what’s excess. When we practice this discernment, when we demarcate borders that keep us in touch with what feels real, true, current, about what is mine or not mine, we can come to know ourselves more clearly. It is a kind of condensing of our essence and our power. Yemima taught:

She returns to herself

she finds her grounding,

her place,

her stillness,

instead of the former inquietude.

She also finds that the happiness of her heart returns,

because it exists inside,

in the light of the heart that returns to its place.

The light is always there,

now it is just

revealed.

Further, seeing our borders more clearly also helps us to be more open, and in richer connection. In Yemima’s words,

If we demarcate borders,

then we begin, in practice,

to relate differently and act differently.

Words are filled with balance and warmth towards the other.

It is not an expressed affection like that which you have towards children,

it is not emotional like with love,

but warmth, embedded in existential self-care and love towards our surroundings.

T’nua תנועה: Movement from Warmth in the Heart: Trust and Tefillah

T’nua is the movement that comes when conditions are ripe.

These practices bring us back to Esther Gopher’s invitation to learn feminine Torah from the female reproductive system. For a female body to be fertile, to create new life, conditions in the body must allow life to happen: her hormonal cycles balance the environment in the womb, it becomes lined with nutrients, and an egg becomes available so that conception can happen. Anyone who has gone through a fertility challenge knows how impossible it is to intervene directly. The action is indirect, there is very little direct impact we can make. You try to make the environment as smooth as possible for the process to happen. You wait for the cycle to work.

In many of Yemima’s teachings, we have learned that “there is no forcing the spiritual,” and that we should avoid effort. The only effort “allowed” is to turn towards ourselves. That is when movement can happen.

But it is not on us to create the movement.

If we do our work, the movement will be done for us.

This is a place of trust, again, where we set the path and we put out a prayer to accompany the work. We trust that the conditions we set will ripen the environment for movement. We trust that the work of balancing will allow the moving soul to be more present with us, that we will feel the movement of the living soul within us, a coherence between ourselves and the Divine. When we recognize this coherence, the yesh, we allow our own souls to lead us, and sense a connection to the Greater Soul. As Yemima says:

When the possibility of prayer opens

the internal will shine.

Parting for Now

We cannot control outcomes, but we try to arrange the right conditions for opening and connection, for spiritual life. We might feel the urge to know: have we made the right effort? When we choose exactly the right thing for ourselves at this moment in time, that which supports nourishment now—what Yemima calls making a diyuk, a precise movement toward ourselves—we will know it because the system will feel quiet. When we are in diyuk, “the body is quiet and the soul is quiet.”

If your system is not yet quiet,

then accept your relative place,

turn toward yourself, don’t worry—you will make it there. And if you are worried, then recognize it (zihuy), demarcate it (tehum), turn to yourself with compassion (hitkarvut), and rest. We are not looking for quiet stagnation, but for a clean and restful system. In Yemima’s language, “Development is movement at rest on our place.” This restful movement, and a connection through felt resonance, is there in the quiet waves, always underneath the noise. It is waiting for us to tune in. Gently.

NAAMA: Once, after a troubling event, I took a long walk in a park. My body was full of resistance to the situation, to my choices. I was walking fast. It was very windy. There was so much blockage inside and so much movement outside. At some point, I remembered this teaching. I stopped and said to myself, “accept where you are right now. Accept your relative place. This is your reality. Turn to yourself, come close even now, even with all the anger at reality, at yourself.” And then the quiet appeared. The situation remained the same, all except my small motion: agreeing to approach myself at the moment. I was able to connect and to decide about my small next moves from a place of connection, of trust that there is a divine life force, that I will find my way. That I am finding my way now.

NAAMA AND HANNAH: The need for security is huge. And it urges us to control and close ourselves up. Letting go requires strong boundaries between ourselves and others, between the past and the current moment. To learn to trust our path, and to know what to do now—this is life’s work. Rewarding work, that allows us to live from within connection. We can learn to bring our attention to the things we can control, and it will help grow our sense of stability.

When I am able to trust life,

I can come to the present moment

with my present capacities

and move with what is happening,

My stability flows from confidence in my ability to act in the world

based on my connection to my soul.

As we reflect on these four practices, we feel how they build on each other. None exists in isolation, and we do not graduate from one to the next. They all interweave into a whole. The path to feminine spirituality is still unfolding orally, for the most part; this is an attempt to capture some of its ways and make them accessible to others. This spiritual practice has been meaningful and life changing for us, it has brought softness and resilience to our everyday choices and a feeling of connection to the Greater Soul.

This is a path embedded in relationship

that is about holding boundaries

and opening up

and sensing the spiritual power embedded in life.

It has taught us

to open,

to wait,

to contain,

to trust that we move through cycles.

We have shared our work here with the hope and prayer that it will open a path for all who seek it.