Jewish Life Tomorrow

FROM THE EDITOR

In the mid-1960s, the editors of Commentary magazine initiated what they called a “symposium on Jewish belief.” Seeking a sense of whether the Death of God movement that was then ascendant among American Protestants had made any headway among American Jews, they sent a five-question survey to 55 prominent rabbis and theologians. Thirty-eight returned it, each addressing the questions they’d been asked: who wrote the Bible; what it means for Jews to be the Chosen people; whether there is any truth in other faith traditions; what the political implications of Judaism might be; and, finally, what stands in the way of modern Jewish belief in God. Their answers were published in the August 1966 issue of the journal and then as a book, The Condition of Jewish Belief.

Only one respondent—Richard Rubenstein—embraced the idea of the death of God. Among the others, the most important finding was the depth of the divide between Orthodox rabbis and their non-Orthodox peers in regard to all of the questions the survey posed.

Today, nearly 60 years later, the symposium offers us a remarkable snapshot of what American Jewish leaders were thinking about in 1966, after the Holocaust and the establishment of the State of Israel, and during the Vietnam War, but just before the Six Day War, which was soon followed by the assassinations of President John F. Kennedy and Martin Luther King, Jr., the political and social unrest of 1968, and the many other events that would come to shake Jewish, American, and world society. The collection showed the influence of 19th and early 20th century German-Jewish thinkers including Samson Raphael Hirsch, Franz Rosenzweig, and Martin Buber on this postwar period but failed to anticipate the revolution that feminism would bring to Jewish practice and Jewish thought. At the same time, some of the work that appeared for the first time in this volume proved to be the groundwork for later developments in Jewish thought. Richard Rubenstein’s assertions, in particular, spurred several Jewish theologians to address the Holocaust more directly than they had before.

This issue of Sources aims to take a similar snapshot of our own moment. We have three particular aims: first, to articulate where we are and where we want to go; second, to identify overlapping influences and intentions that we might not otherwise see; and, third, to create a document that might allow future generations—those who will already know what awaits us tomorrow, next year, and for a long time beyond—to understand us, both who we are and who we want to be.

And so, where are we? Where do we want to go?

These questions echo the attitudes of 19th-century scholars, rabbis, and rabble-rousers who sought to redefine Judaism for the modern age. Their efforts led to competing religious movements—Conservative, Orthodox, Reform, and so forth—and competing political movements—Bundist, Zionist, and more. In short, our 19th-century ancestors bequeathed to us a Judaism and a Jewish politics defined by the assumption that we can choose the meaning of our Jewishness, should we wish to hold onto it at all. Insofar as we continue to believe that we can choose what our Jewishness will mean—what it will stand for and how we will express it—we remain, like them, liberal Jews.

The question I began with was collective: where are we? Where do we want to go? The “we” was purposeful; liberalism may emphasize the individual, but Jewishness remains a collective identity. The Hebrew Bible uses the language of covenant to describe the foundations of the Jewish people, and covenant entails commandment. The rabbis of the Talmud talk of a Jewish law, a halakhah, that governs communal and individual life. Liberal Judaism can be understood as an attempt to assert control over the sense of obligation that we have inherited. But the language of obligation has not disappeared, and it insists that we attend to it.

Love Jewish Ideas?

Subscribe to the print edition of Sources today.

As Jews, it seems we continue to want to be obligated. We see this in the popularity of the theology of Eugene Borowitz among liberal rabbis. He described his book Renewing the Covenant as “postmodern” in recognition of its pushing back against the assumptions of classical liberalism. We see it in the growing numbers of Jews who are returning to ritual practices such as keeping kosher or keeping Shabbat—practices rejected by their grandparents or great-grandparents—or choosing to take on not just a particular obligation but an entire lifestyle defined in halakhic terms. Leon Morris celebrated the virtues of a sense of obligation in the pages of this journal not that long ago.

We can also see it in the broad popularity of Mara Benjamin’s 2018 book, The Obligated Self: Maternal Subjectivity and Jewish Thought. As unlikely as it might sound at first, Benjamin’s book makes a compelling case for understanding the covenantal obligations in ways that parallel the obligations of a parent to a child, what she calls the Law of This Baby or, in its more general form, the Law of Another. A description of the complicated feelings a parent often has toward these obligations captures, at least for me, the tensions between Jewish liberalism and Jewish obligation. After describing how very much she wanted to be a mother, she writes that “I could not agree to the law before I was already subject to it. And once in place, I could only violate the law through inattention or frustration; I could not cast it off. I transgressed the law as often as I fulfilled it, leaving my crying baby or comfort-seeking toddler to calm herself when I could not bring myself to respond. Nonetheless, it was clear to me that there was a law, and the law applied to me by virtue of being my child’s parent” (9).

Perhaps we Jews today are in a similar position: we want to be obligated, and when we find ourselves obligated, we remain free to fulfill those obligations imperfectly or not at all. And in that, we retain our liberal individualism.

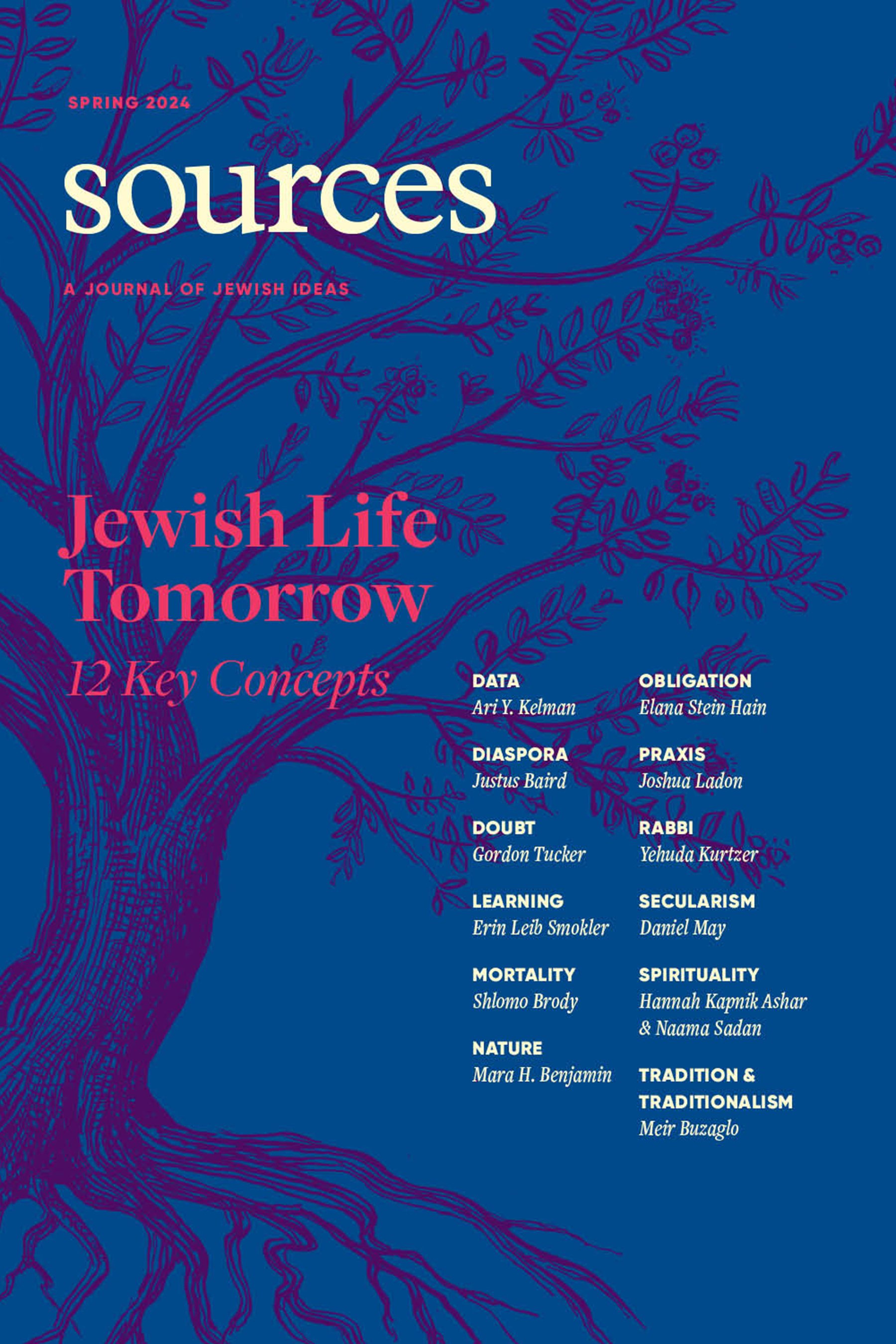

The editors of Commentary snapped a picture of Jewish thought in 1966, and we are snapping one of Jewish thought in 2024. But just as the technology for taking actual snapshots has changed dramatically since the 1960s, the structure of this issue is distinctly different from the earlier one. We did not circulate a survey, and in the pages that follow, you will not find dozens of rabbis pontificating on a single set of questions. Instead, what awaits you inside this issue are essays on twelve concepts, arranged in alphabetical order. Some are concepts you’ll find in most any account of Judaism (e.g., rabbi and learning); others reflect needs particular to this moment (e.g., data and nature). Each is written by a scholar who has both relevant expertise in the history of the concept they are discussing and a vision of how it should play out in the Judaism of tomorrow.

The essays overlap and conflict; they reflect and express the twin senses of obligation and freedom that I’ve tried to capture in this note. They do not emerge from any particular movement of Judaism or Jewish politics, and they are not satisfied with current expressions of Jewishness. You will see the influence of earlier eras of Jewish thought and practice but not with a longing to return so much as a desire to bring the best of those times into the present and future.

Finally, I want to note that I began commissioning essays for this issue in early 2023, and many of the pieces were first drafted before October 7. After Hamas’s attack on Israel that day, this issue was put on hold as I turned my attention to a special wartime issue of Sources, which was published online last December. (If you have not yet seen the Israel at War issue, I encourage you to go to sourcesjournal.org, where you can find it under Past Issues.) As you read the essays, you will see that many authors chose to update their pieces in light of October 7; Gordon Tucker’s essay on doubt responds directly to the experience of viewing the war from a distance.

I look forward to hearing what you think.

Claire E. Sufrin