Responding to the Dobbs Decision: American Jews & Religious Freedom

JEWS AND LAWIsaac Weiner

Isaac Weiner is associate professor of comparative studies and director of the Center for the Study of Religion at Ohio State University.

In the immediate wake of the Supreme Court’s June 2022 decision in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health, several liberal Jewish groups went to court, asserting a religious right to an abortion. Some did so even before the Court had handed down its final ruling. Congregation L’Dor Va-Dor, for example, of Boynton Beach, Florida, filed a lawsuit in Leon County Circuit Court a full week before the Court issued its Dobbs decision. The synagogue challenged a new Florida law prohibiting abortion after 15 weeks by arguing that Jewish teachings require abortions “if necessary to protect the health, mental, or physical well-being of the woman.” As such, the suit concluded, Florida’s law violated the religious freedom of Jewish women by prohibiting them “from practicing their faith free of government intrusion.”

This litigation strategy holds great pragmatic appeal. Over the last several years, the Supreme Court’s six conservative justices have proven themselves remarkably sympathetic toward litigants advancing religious liberty claims, especially when those litigants were Christians claiming conservative views on matters of sexual morality. Think, for example, about the owners of Hobby Lobby Arts & Crafts Stores, who refused to provide their employees with insurance coverage for certain forms of contraception; or Jack Phillips, the Colorado baker who refused to create wedding cakes for same-sex couples; or Catholic Social Services, which refused to place foster children with LGBTQ parents. In each of these cases, claimants succeeded in invoking their religious beliefs to avoid having to follow otherwise applicable laws.

The Jewish abortion lawsuits sought to take advantage of this new pattern in the Court’s jurisprudence by mobilizing it toward progressive political ends. If Hobby Lobby, or Jack Philips, or Catholic Social Services had legitimate claims for legal exemptions, the logic went, then surely Jews do, too. At the very least, this strategy offered liberal Jews the chance to do something in the wake of the Court’s devastating decision in Dobbs. The right of religious freedom seemed to offer a path forward.

Yet, beyond the immediate issue of securing abortion rights, these lawsuits also speak to the abiding faith of American Jews in the promise of religious liberty. Throughout U.S. history, Jews have turned to the language of religious freedom to defend their legal rights and to claim political equality with other religious communities. Since at least the middle of the twentieth century, Jewish organizations have strategically turned to church-state litigation to protect and advance what they perceived as common communal interests, on issues ranging from prayer in public schools to discrimination in the workplace. Not surprisingly, over this time, American Jews grew deeply comfortable with and attached to the language of religious freedom. The recent abortion lawsuits can be read as of a piece with this past, reflecting the American Jewish sense that religious freedom has generally served us well.

But has it? Does religious freedom warrant the faith we have placed in it? As a scholar of American religious and legal history, I have some ambivalence about these questions. On the one hand, religious freedom has offered a powerful rhetorical tool through which Jews and other marginalized groups have sought to secure their place in American society. On the other hand, as I will detail further below, courts have proven themselves unreliable partners in this project, frequently failing to safeguard the rights of religious minorities, including Jews. Religious freedom may have great political value, but its actual effectiveness has been more limited when it comes to winning legal arguments.

In fact, as I consider the larger context of the Dobbs decision, I have to ask if it’s really a good idea right now to put our faith in the language of religious freedom. I wonder this for at least three reasons. First, although Hobby Lobby and other recent decisions give the appearance of a court uniquely devoted to the principle of religious freedom, the reasoning behind these decisions marks a distinct shift away from the separationist principles that have long formed the foundation of American Jewish thinking about church-state relations. We need to ask ourselves as a community what it means to advocate for religious exemptions outside of that separationist framework, especially as the Court continues to privilege the interests and concerns of Christian claimants over those of minority groups. Second, we need to be cautious about the ways that the discourse and practices of religious freedom might inadvertently hollow out the richness of Jewish tradition and lived experience, flattening it to fit into Protestant and secular frames for which it may be particularly ill-suited. And third, we should be mindful of how the project of guaranteeing religious freedom inevitably requires the state to distinguish worthy claimants from unworthy ones. Historically, this has rarely worked out well for marginalized groups. Taken together, these concerns should help us appreciate that religious freedom has always been a more problematic concept than American Jews have recognized. It’s not clear that it’s ever really been capable of doing the work we want it to. Rather than recommitting ourselves to it, perhaps we might find in this moment an opportunity to reconsider our faith in religious freedom altogether.

The first reason to question whether this is a moment to claim religious freedom is likely the most familiar to many readers, namely, recent shifts in the Supreme Court’s jurisprudence. Over the last decade or two, there has been a marked change in how the Supreme Court interprets the meaning of the First Amendment’s religion clauses. Conservative justices have elevated the free exercise of religion to a privileged position by dramatically expanding the conditions under which religious claimants may demand exemptions from otherwise applicable laws. During the COVID-19 pandemic, for example, the Court found that lockdown orders impermissibly discriminated against religion if they made exceptions for secular practices, like grocery shopping, but not for religious observances, like attendance at church. At the same time, the Court has dismissed altogether concerns about the dangers of religious establishment. In its recent decisions, it has interpreted the separation of church and state as infringing on individuals’ religious liberties rather than safeguarding them. Taken together, these shifts constitute a marked departure from the kinds of positions that once commanded widespread Jewish support.

The history of church-state litigation strategies pursued by American Jewish organizations reveals a very different understanding of religious freedom. What once passed as the consensus position of the organized Jewish community was forged in the mid-twentieth century, in the decades immediately following World War II. Communal agencies like the Anti-Defamation League, the American Jewish Committee, and the American Jewish Congress in particular embraced litigation as a strategy for defending Jewish communal interests. In so doing, they ended up playing a prominent role in shaping the Supreme Court’s First Amendment jurisprudence. Attorney Leo Pfeffer, for example, who served as director of the AJ Congress’s Commission on Law and Social Action, argued dozens of religious liberty cases before the Supreme Court, wrote more than 120 briefs, and regularly consulted with other Jewish and non-Jewish groups alike on legal strategies and tactics. He was so successful in his efforts that one observer described it as often “hard to determine where Pfeffer’s words ended and the Court’s began.”

Pfeffer’s interpretation of the First Amendment, widely endorsed by other community leaders, relied on reading its two religion clauses—the clause restricting an establishment of religion and the clause protecting religious free exercise—as a “unitary guarantee.” Where some observers perceived tension between the two clauses, Pfeffer believed they were properly understood as working in tandem to safeguard the rights of minority groups. He believed Jews and others ought to enjoy special protections for their religious liberties, but he was even fiercer in his advocacy for a strict separation between church and state. The “complete separation of church and state is best for the church and best for the state,” he asserted, “and secures freedoms for both.” He drew on his personal experience of growing up as an observant Jew in a predominantly Christian society to challenge any form of state support for religion, especially in the area of education. He opposed financial aid for parochial schools and, somewhat more controversially, also led the charge against organized prayer in American public schools. He regularly invoked the Supreme Court’s 1947 endorsement of a “high and impregnable” wall between church and state as he worked to undo government programs that supported Christian instruction and worship under the guise of state neutrality. Contra his critics, who argued that strict separation would foster a public square hostile to religious interests, Pfeffer argued that a high wall of separation was the key to ensuring equal participation in public life for Americans of all religions—and those of none. It was strict separation that would guarantee Jewish equality, Pfeffer believed, not religious liberty alone.

Pfeffer’s positions once commanded significant support from the Court itself, but that is clearly no longer the case. In two other landmark decisions, released the same week as Dobbs, the Court effectively completed a decades-long project of dismantling Pfeffer’s legacy in its entirety. In Carson v. Makin, the Court ordered the state of Maine to include religious schools within a public program that provided direct tuition assistance to parents. And in Kennedy v. Bremerton School District, the Court recognized the religious rights of a public school football coach to visibly kneel in prayer at midfield following his team’s games. In both cases, the Court’s conservative majority diminished or dismissed establishment clause concerns entirely. They rejected the argument that Maine had a legitimate interest in not funding religious education or that the coach’s position might exert undue pressure on his students. Instead, the justices centered their arguments on the religious liberty interests of the parents who wanted to send their children to Christian schools and the coach who wanted to acknowledge God after a hard-fought game. On their reading, strict church-state separation became an impediment to the right to exercise one’s religion freely rather than serving as a safeguard for religious equality.

To be sure, many American Jews, especially those identifying as politically conservative and/or religiously Orthodox, voiced support for these decisions. They agreed with the Court’s interpretation of religious freedom and embraced the space opened up by Kennedy for accommodating the public expression of religion and the potential to capitalize on Carson by securing greater public aid for Jewish education. These responses made evident that the assumed consensus of the American Jewish community on church-state relations had fractured. In fact, we should recognize that it was never as stable or secure as it had once seemed. For decades, conservative Jewish critics have contended that their liberal counterparts had gone too far in committing themselves to a position of strict separationism. They argued, in the words of Jewish theologian and sociologist Will Herberg, that “the promotion [of religion] has been, and continues to be, a part of the very legitimate ‘secular’ purpose of the state” and imagined a far more robust role for religion writ large in American public life. They joined common cause with conservative Christians in decrying the secularity of public schools, advocating for aid to private schools, and seeking more robust accommodations for public religious observances. They came to regard the secular state and not Christian hegemony as the greater threat to Jewish interests.

Despite the strength of the Orthodox Union and similar organizations, the majority of American Jews remain committed to the more classically “liberal” separationist position. Yet with a 6-3 conservative majority locked in place, it is hard to imagine the Court returning to Pfeffer’s strict separationism any time soon. When liberal Jews turn to the language of religious freedom today, they must recognize that they do so within this changed legal landscape. They cannot rely on the kinds of protections the Establishment Clause once guaranteed. Can this new framework be turned to Jews’ advantage? It’s hard to say. Such a strategy is clearly not without its risks. Even if it was never applied consistently in practice, the discourse of disestablishment once offered Jewish advocates powerful language for articulating concerns about Christian privilege and influence. Without its checks, religious freedom is just as likely to be used today to shore up Christian power as it is to weaken it. Liberal Jews need to proceed cautiously, then, in pursuing litigation strategies that might have the unintended effect of bolstering Christian hegemony. By seeking exceptions from laws that are otherwise presumed to be neutral and generally applicable, they risk reinforcing a legal framework that may not be in Jews’ long-term interests. That may be an acceptable cost if it serves to secure Jewish reproductive rights in the short term. But it might also mean that it’s time to pursue alternative political strategies instead.

Love Jewish Ideas?

Subscribe to the print edition of Sources today.

My second concern about religious freedom relates to how we engage with the precepts of our own religious tradition. In short, how does the discourse of religious liberty constrain our Jewish imaginations?

In the months after Jewish groups first filed lawsuits contending a religious right to abortion services, there was a proliferation of opinion pieces, webinars, and synagogue discussion groups focused on the question of what Judaism “really” teaches about abortion. Rabbis debated the circumstances under which Jewish law permits or even mandates the termination of a pregnancy and explored the different ways we might interpret the factors determining maternal health. American Jews were eager to mine Jewish sources for alternative ways of framing conversations about reproductive justice. Such interest was likely inevitable in the wake of the Court’s Dobbs decision, but it took on particular valence in light of the Jewish lawsuits. This is because to obtain an exemption from an otherwise applicable law, claimants must establish that the law in question has placed a “substantial burden” on their ability to exercise their religion. For Jews to argue that abortion bans violated their religious rights, they would have to assert that having access to abortion services was a necessary part of their religious practice. Is that so, people wondered? Must Jews have the option to obtain an abortion, at least in certain circumstances? What does “Judaism” say about that?

As they addressed that question, many of the articles and classes that emerged last summer tended to presume the existence of a single Jewish position on abortion rather than the more complex and varied attitudes that we find toward everything else among contemporary Jews. Moreover, in presenting “the” Jewish view on abortion, most writers turned to Jewish law, equating Jewish religious practice with adherence to halakhah. They looked to the Talmud to decipher what the interests and concerns of the ancient rabbis might mean for the rights of American Jews today. This sort of approach was present even among liberal Jews, who generally reject halakhah as a fixed or binding system of rules and laws. In fact, some conservative commentators tried to use against them the tension between the claim that halakhah sometimes requires pregnancies to be terminated and liberal Jews’ more general tendency to reject the notion that halakhah is obligatory at all, in order to undermine the legitimacy of their claim that Jews should be exempt from abortion bans. In a widely read essay, for example, legal scholar Josh Blackman castigated liberal Jews for opportunistically “gerrymandering” the First Amendment’s Free Exercise Clause to advance their progressive agenda. Because their turn to halakhah seemed transparently calculated, he accused them of masking what were essentially political positions behind the language of religious freedom.

Here again, the stakes are even higher than they might seem. As Jewish studies scholar David Schraub has documented, Blackman is part of a larger movement that has worked to categorically discredit liberal religion—and liberal Judaism specifically—as not a “real” religion, or at least not the kind of religion meant to be protected by the First Amendment’s Free Exercise Clause. To this end, Blackman’s argument included the audacious suggestion that liberal Jews can never, strictly speaking, have a valid religious liberty claim because their commitments ought never to be taken seriously. If liberal Jews don’t genuinely feel “beholden” to any normative sources of authority—like God or halakhah—then how could their religious practices ever be substantially burdened? If they don’t consider religious law to be binding in general, then how could they ever claim an obligation to follow any one of its dictates?

There is no question in my mind that such arguments betray a shallow understanding of the nature of religious commitment and of legal obligation, at odds with the way many, dare I say most, Americans practice their faiths. For Jews like me, for example, there is no contradiction between our failure to observe all of the laws of kashrut strictly, and our sense that we should enjoy a right not to be forced to eat a ham-and-cheese sandwich. Religious commitments are often flexible and improvisatory, but that doesn’t make them any less meaningful or sincere.

And yet, though it is impoverished, the understanding of religion advanced by Blackman and others like him is frequently endorsed by the jurisprudential language of religious freedom and has, as a result, implications far beyond a single essay on how liberal Jews argue for abortion rights. It may be true, as a technical matter, that religious exercise is protected by federal statute even if it is not “compelled by, or central to, a system of religious belief.” Indeed, courts have repeatedly announced that what matters is whether beliefs are sincerely held, not whether they are consistent or supported by textual authority. Yet in practice, federal jurists have tended to presume the “sincerity” of certain groups more than others, as I will detail below, and they have been quicker to recognize forms of religion that are hierarchically organized, normatively prescribed, and perceived as binding. As religious studies scholar Winnifred Fallers Sullivan has shown, courts can have a hard time making sense of the protean, do-it-yourself character of much of American religion.

In her provocative 2005 book, The Impossibility of Religious Freedom, Sullivan offers a close reading of the testimony in a federal district court case about religious gravestone markers in a public cemetery in Boca Raton, Florida. The Jewish and Christian plaintiffs insisted that their ways of marking their ancestors’ graves were religiously prescribed, though they could not point to any legal or textual sources to substantiate their claims. Their sense of obligation was imposed through the weight of tradition and experience, passed down through informal “folk” pathways, rather than through the formal teachings of recognized authorities. This posed a real problem for the judge in the case, who failed to recognize their claims as constituting “real” religion and ruled against them. He preferred instead what Sullivan describes as an “essentialized” religion, one with clearly defined rules and sharply demarcated boundaries.

When we reduce Jewish traditions around reproductive justice to questions of halakhic authority, we risk reinforcing this limited way of thinking about the nature of religious commitment. This does not mean that we shouldn’t look to Jewish texts and legal sources for guidance, of course. I appreciate the important role that legal texts play in the lived experience of Jewish communities, and I think they do offer productive resources for reframing the terms of American conversations about reproductive health. But it is important to engage these sources in ways that do not valorize Orthodox forms of commitment as normatively preferable or that grant halakhic Judaism the exclusive right to speak on any matter of public concern to Jews and others. We need to be cautious in mobilizing discourses of religious freedom that naturalize these ways of thinking about religion—and about law—or that make them seem obvious and self-evident. Above all, we need to be careful not to defend religious rights in ways that risk denigrating the lived experiences of most American Jews. To do so would be to devalue the richness of our tradition—and the space it affords for diversity and disagreement—rather than to preserve it.

This brings me to my third and final point. I’ve suggested that discourses of religious freedom tend to privilege certain forms of religious life over others. This is not a bug of the system, however, but one of its defining features. As long as legal rights are predicated on identifying certain beliefs and practices as religious, then courts and other state actors will have to determine just what religion is. They will inevitably have to draw lines between what counts—what warrants protection—and what does not. There is no way of doing this that does not involve drawing highly contested distinctions between claimants considered worthy and unworthy, legitimate and illegitimate.

Liberals are right to feel offended when conservative critics mischaracterize the depth and sincerity of their convictions. They are right to be upset when the legitimacy of their claims is unfairly challenged. But this is not altogether different from the ways liberals have attacked conservative claimants like Hobby Lobby or Jack Philips, the Colorado baker. Many critics wielded accusations of insincerity or bad faith against them, too, arguing that what they were practicing was not “really” religion, or at least not religion of the right kind. It is one thing to say that their religious liberty interests ought to have been better balanced against the needs and interests of others. But many went much further and challenged the validity of their beliefs altogether. Liberals decried their mixing of religion and business, or their use of religion to discriminate against others, or the ways they seemed to be “weaponizing” the language of religious freedom to mask what were essentially political positions. Just after the Supreme Court issued its decision in the Hobby Lobby case, for example, Sally Steenland, director of the Faith and Progressive Policy Initiative at the Center for American Progress, alleged, “When for-profit corporations get the same privileges that have historically been given to religious groups that feed the hungry and care for the sick, religion itself is cheapened and devalued.” While I, personally, might be sympathetic to these complaints, it is not obvious to me how U.S. courts ought to adjudicate them. On what basis should federal jurists determine the nature of “religion itself” and when it has been “cheapened and devalued”? By what criteria should they determine whose religion is worthy of protection?

My point is not to suggest all religious liberty claims are equally valid, but rather to note the ways that discourses of religious freedom invite precisely these kinds of attacks on the legitimacy of others’ beliefs. Liberals and conservatives alike end up accusing each other of bad faith, of using the language of religion to advance what are really political interests. In both cases, they wrongly assume that religious freedom has some kind of stable essence, that some groups are using it properly while others are using it improperly, which in turn presupposes some notion of what is authentically religious that can be distinguished from that which is not. They risk freezing religious—and legal—meaning in time, ascribing to them a fixed and unchanging nature. In fact, church-state separation has always been somewhat of a myth because separating religion from government—even in order to protect it—requires the state first to define just what religion is. This is a dangerous game, and one that has rarely worked out well for minority communities. When lines are drawn, marginalized traditions almost never find themselves on the right side of them.

Consider the 1879 case of Reynolds v. U.S. In its first foray into interpreting the meaning of the First Amendment’s Free Exercise Clause, the Supreme Court ruled against George Reynolds, a Mormon man who claimed a right to practice plural marriage (polygamy). Reynolds could believe whatever he wanted, the Court promised, but he was not necessarily free to act on those beliefs. While Congress had no legislative power over “mere opinion,” the Court maintained, it could prohibit practices it deemed “subversive of good order.” It did not trouble the Court that legislative bodies will usually define “good order” in line with majoritarian values. By distinguishing between beliefs and practices, the Court could insist that it was protecting Reynolds’s religious freedom even as it prevented him from fulfilling what he considered to be a fundamental religious obligation. Religion, at its core, this Court announced, was a matter of inward belief. Defined in this way, the First Amendment could be used to keep marginalized communities in check as much as it could secure their right to be different.

Or consider the historical experience of Native Americans, who have often struggled to get courts to recognize their claims and practices as properly “religious” and thus entitled to protection. This has especially been the case in disputes over sacred lands. In the landmark 1988 case of Lyng v. Northwest Indian Cemetery Protective Association, for example, the Supreme Court permitted the United States Forest Service to proceed with a development project despite the fact that it would “irreparably damage grounds that had historically been used by Native Americans to conduct religious rituals.” Writing in dissent, Justice William Brennan famously described the case as representing “yet another stress point in the longstanding conflict between two disparate cultures—the dominant western culture, which views land in terms of ownership and use, and that of Native Americans, in which concepts of private property are not only alien, but contrary to a belief system that holds land sacred.” Because they associated religion with personal commitment and belief, the Court’s majority could not make sense of the communally oriented, land-based claims advanced by these and other American Indian groups. Religious freedom hardly served them well.

In fact, the groups that have historically benefitted the most from religious freedom have been those that could best fit their claims into frames that were legible and recognizable to U.S. judges. This has tended to mean groups who most closely resemble white Protestant Christians. Racialized minorities, sexual nonconformists, incarcerated individuals, and other marginalized people have had a much harder time securing religious freedom’s protections, frequently finding their claims challenged as insincere or illegitimate. In fact, a number of scholars have recently suggested that religious freedom functions primarily, not incidentally, as a tool for assimilation, by disciplining minority communities into acting more in line with the norms of the majority. In order to secure recognition from the state, they must learn to practice their religions in normatively authorized ways.

No matter what we might want to think, this has been true for American Jews, too, whose collective ways of life have never quite fit within the legal model of religion as a matter of personal, sincerely held belief. When courts have sought to find religion, they have looked for something personal, voluntary, and freely chosen, not a form of peoplehood, passed down through inherited birthright or lineage, and not something grounded in notions of community or ritual practice. Moreover, as I’ve suggested, courts tend to want clearly defined rules and sharply demarcated boundaries, not flexible, nuanced forms of hermeneutical interpretation. They interpret religious meaning in ways that freeze both religion and law as fixed and unchanging. As strongly as Jews have believed in the promise of religious freedom, they’ve never actually been all that successful with it in the courts, except for when they have shaped their claims to conform more closely to Protestant norms and expectations. Legal conceptions of religion have never really been capacious enough to accommodate Jewish difference. Religious freedom may not be able to do for us what we want.

We live in a fraught moment. The Supreme Court’s new conservative majority has rapidly upended the law of religious liberty and exposed deep political divides within the American Jewish community. Many liberals feel utterly despondent, harboring little hope of changing the Court’s direction anytime soon. In such an environment, it makes sense to experiment with the language of religious exemptions, to see if the Court’s new jurisprudence might be turned back against itself. I find myself deeply sympathetic with this course of action as a pragmatic strategy and stand in solidarity with those working to advance it. We’re clearly in a “throw everything at the wall” moment, and I support any approach that might help women and pregnant people get access to the services they need. If we can make religious freedom work for us, then I’m all for it.

But for the reasons I’ve suggested, I have real doubts about whether this strategy will succeed, or even whether it’s in our collective long-term interests. I have concerns about how the discourse of religious freedom constrains our Jewish imaginations and about the ways religious freedom has been mobilized to keep minoritized communities in check. I have concerns about how appealing to the Court’s current understanding of religious freedom might serve to bolster Christian hegemonic interests, rather than undermine them. And, more narrowly, I worry that seeking exemptions from abortion bans in the name of religious freedom might prompt conservative legislators to eliminate exceptions from such laws altogether, resulting in laws that are more, not less, regressive. For all these reasons, and more, I have a hard time trusting in courts to come to our rescue now. Instead of recommitting ourselves to the promise of religious liberty, perhaps it’s time to take stock and reassess our faith in it altogether.

Admittedly, I am not a lawyer or professional political strategist. I'm not sure of the specific courses of action we ought to be pursuing instead. But from my perspective as someone who studies the intersection of law and religion, I do find it necessary to challenge the confidence with which we’ve appealed to religious freedom in the past and the complacency with which we’ve put our trust in federal courts to safeguard our rights. We might still be able to make religious freedom work for us, but only if we approach it with greater clarity about both its capacities and limitations. Let’s make sure that as we pursue equal rights and justice for all, we do so in ways that respect the distinctiveness of our own traditions, that we work to preserve and make space for that which makes our traditions worthy of protection in the first place. I’m not convinced religious freedom is capable of that.

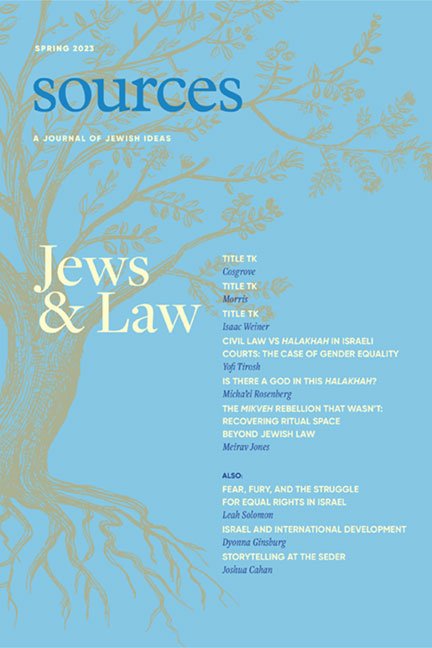

This article appears in Sources, Spring 2023.