American Jews & Our Universities: Back to Basics

Josh Feigelson

Josh Feigelson is President & CEO of the Institute for Jewish Spirituality. He previously served as Dean of Students at the University of Chicago Divinity School.

I can remember exactly where and when I first realized that not everyone goes to college. It was 1990; I was 14 years old and on a Boy Scouts campout. The leader was a senior in high school, and when we started talking about what he planned to do after graduation, he told me he was going to enlist in the United States Army. Growing up Jewish in Ann Arbor, Michigan, it had never even occurred to me before then that one wouldn’t go to college. Everyone in my universe—my parents, my older brothers, my extended family, the people at our synagogue and in our community—they all went to college. The idea of doing something else? In the words of Tevye: “Absurd! Unthinkable!”

While my personal experience might be extreme, I think it reflects a truth about American Jewish life: for generations now, higher education has been a central pillar around which we have oriented our self-conception. According to the Pew Research Institute’s 2020 study of American Jews, 80 percent of American Jews have attended at least some college, as against 60 percent of the general American population. More strikingly, 58 percent of American Jews have not only attended college, but graduated—double the general population figure of 29 percent. And over a quarter of American Jews have post-graduate degrees, 2.5 times the general figure. Furthermore, these figures are not new: The 1964 American Jewish Yearbook estimated that 80 percent of college-age American Jewish youth attended college.[1] The centrality of higher education to American Jewish identity is long and deep, a situation that led Yitz Greenberg to write in 1968: “If college sneezes, the Jewish community catches pneumonia.”[2]

Greenberg defined the ultimate effect of this pneumonia as making the college campus a “disaster area for Judaism, Jewish loyalty, and Jewish identity,” and he suggested ways to counter this diagnosis: invest in Hillel, develop Jewish Studies, put knowledgeable and skilled Jewish adults on campus to build relationships with and model adult Jewish life for young people, etc. Our communal Jewish discussion today is similar, generally focusing on ways to make college safe and welcoming for Jewish students—that is, keeping Jewish students inoculated from the perceived harms of college life or, if they have become infected, caring for and nursing them back to health.

Thanks in no small part to the enactment of many of the recommendations Greenberg made in 1968, college campuses today feature many more supports for Jewish students. But Greenberg didn’t examine some of the larger structural and historical questions underlying what he identified as the campus “catching cold.” I believe that if we are to respond fully to today’s campus turmoil, we must examine how American universities came to be, their larger aims and purposes, and the enormous tensions built into them from the beginning. Perhaps a half-century ago it was hard to imagine that Jews could exercise much influence in the direction of these institutions. In 2024, I would suggest, it is not—and, in fact, the larger discussions about the fundamental aims and purposes of higher education are essential for us to engage in as a community, both internally and with larger society. By delving more deeply into the history of higher education, I believe we can envision a healthier present and future not only for Jewish students, but for all students and American society as a whole.

What is Higher Education?

Overwhelmingly, American Jews have attended research universities. In the United States, these institutions first arose in the mid-19th century and, in their purest form, were modeled on the German research university. According to this understanding of higher education, the university—Johns Hopkins, founded in 1876, is the paradigmatic example—exists to push scientific knowledge forward by providing a home for experts (professors) to pursue their thoughts unfettered by church or state as well as to train new generations of experts (PhD students who will become professors) in the sciences, both “hard” (e.g., biology, chemistry, physics) and “soft” (e.g., psychology, sociology, economics).

But the German model is not the only one. In his classic history, The Emergence of the American University (1970), Laurence Veysey argues that this research agenda runs in tension with a second vision, which he terms “service.” Think here of professional schools: medicine, law, divinity (all existed at various institutions before the Civil War) or engineering, business, social work, etc., which arose in the later 19th and early 20th centuries. The primary purpose of these schools is to provide value to society through the practical application of knowledge, e.g., improved farming techniques through schools of agriculture, new inventions through schools of engineering, better methods of teaching through schools of education. Cornell, founded in 1865 as one of the few private Federal Land Grant institutions, is often regarded as a case study.

Both of these newer agendas contrast with a third, older model of higher education. This model, often termed “liberal education” and English in provenance, shaped many American institutions, including Harvard (founded 1636) and Yale (1701) in their original designs. In the liberal education paradigm, the focus of higher education is not on original research, as in the research model, or on practical applications of knowledge, as in the service model. It is focused instead on shaping young people (men, originally) in the knowledge and habits—the “furniture of the mind” in the memorable words of Yale President Jeremiah Day in 1828[3]—that would help them be “liberal” people, that is, free citizens who do the things that virtuous free citizens do.

Eventually, these three agendas commingled and overlapped into a new, multipurpose model of higher education. Just look at the histories of universities that added graduate programs and professional schools onto their core undergraduate colleges. Yale College, for instance, today remains the only undergraduate division of the university. But Yale created its Graduate School of Arts and Sciences in 1847 and, between 1869 and 1923, added professional schools of fine arts, music, forestry, public health, architecture, and nursing. Arriving at a similar mix from the other direction, land-grant institutions created with an agricultural or technological focus developed undergraduate programs under a general mandate not to produce liberal thinkers, but rather to produce professionals who would contribute to economic growth and scientific advancement. Take, for example, Iowa State University, whose College of Agriculture and Life Sciences was founded in 1858; it ultimately opened an undergraduate College of Liberal Arts and Sciences a century later in 1959.

American Jews need to know this history because many of the tensions that underlie contemporary university life trace their roots back to these competing agendas. If a university’s primary purpose is the untrammeled pursuit of knowledge and truth, then values like academic freedom and a prioritization of time towards research for tenured faculty are of great importance. But if a university’s primary purpose is to ensure that professionals entering fields like business, engineering, or education have the skills they need to be successful, we are likely to judge it in terms of its return on investment, the cash value of the education it provides.

There are further tensions within the liberal education agenda itself because at its root, liberal education is composed of contradictory lineages and impulses. Historian Bruce Kimball notes that as far back as the ancient Greeks, the notion of liberal education has oscillated between two meanings. The first, which Kimball terms ratio, is liberal education as freedom of thought and inquiry, a search for truth. The second, which he calls oratio, conceives of liberal education as developing the habits of speech and conduct that characterize free, that is, liberal, people.[4] The former is fundamentally an expression of critical inquiry, animated by what we might today call a hermeneutics of suspicion that when reading a text asks the question, “What isn’t here? What is the author’s agenda, and what are the larger forces that might be driving them to say what they’re saying?” The latter, by contrast, is an expression of appreciative inquiry, animated by a hermeneutics of charity, asking not what is absent but what is present—"what is good and true in this text or thing that I’m encountering?” As Kimball demonstrates, and as one might intuit from personal experience, the term “liberal education” is invoked to mean both diametrically opposed conceptions.

A few years ago, I heard Eboo Patel, founder of Interfaith America, helpfully summarize what seems to have happened in American universities: the critical inquiry approach to liberal education has consumed the appreciative approach. The main questions that seem to be welcome these days, particularly in the humanities and social sciences, are those that are suspicious, those that ask what isn’t here: who is being marginalized, who is being oppressed, whose voices are not represented? There seems to be little space in these fields of liberal education for asking: what from the past is good and true? What do we want to take with us into the present and future? The hermeneutics of suspicion have cannibalized the hermeneutics of charity or grace.

It's not as simple as that, of course, but my own long experience in and around American higher education leads me to see more than a grain of truth in Patel’s observation. And I think we can add a couple of more important developments to his analysis. The first draws on the larger institutional history I sketched above. At research universities, faculty and graduate students who are studying and thinking at the most advanced levels of their fields typically also teach undergraduates who are not yet, and most often never will be, specialists in those fields. While a hundred students might take an introductory sociology course, only a fraction of those will go on to be sociology majors. And even among those majors, only a fraction will go on to graduate school and the professoriate.

One of the effects of this can be that terms developed for application in advanced research settings—think of Critical Race Theory or decolonialization, for instance—wind up being taught to students who are not in, and will never find themselves in, those same advanced settings. Yet those students now have the professional’s tools in their hands, and they are eager to try to apply them—even, perhaps, in settings well beyond their intended use or in other mistaken ways.

But that has probably been true for as long as research universities and liberal arts colleges have coexisted. So why does it seem, in the current moment, that this phenomenon is suddenly on steroids? Social media, of course, has played a huge role. Once armed with powerful academic terminology, a hermeneutics of suspicion, and a set of media platforms that thrive on and feed sound bites, images, and tribalism rather than reasoned, long-form discursive reflection in a college seminar, it isn’t hard for a committed group of passionate young people to change the world—or at least parts of it. All of this comes against the backdrop of other technological, social, political, and economic changes, including the rise in college tuition at a rate that has rapidly outpaced inflation. Collectively, these shifts seem to have eroded social capital and diminished emotional resilience—what Jonathan Haidt and others have argued are basic building blocks for creating both healthy learning environments and a healthy society in which critical and appreciative inquiry exist in productive tension with one another.

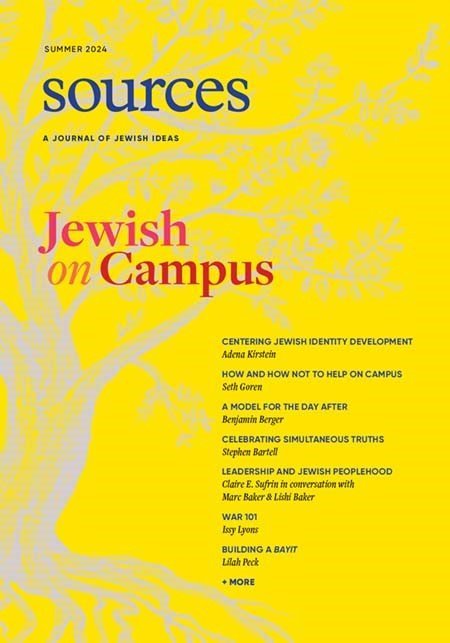

Love Jewish Ideas?

Subscribe to the print edition of Sources today.

Where Do We Go From Here?

Whatever their shortcomings, colleges and universities still offer extraordinary opportunities for learning, growth, and development. They are still the places where our young people, who are increasingly growing up in socially isolated bubbles, encounter extraordinary diversity and develop new relationships. As we approach the 250th anniversary of the founding of the United States, it seems to me self-evident that diversity and encounter with difference and otherness is not only healthy but profoundly necessary to weave a larger sense of wholeness: e pluribus unum. For American Jews, this implies that, in one way or another, we have to engage with that diversity and enter those encounters. It is simply a fact (a very welcome fact) of American life, and college remains one of the preeminent places for us to do it.

Beyond the diversity argument, there is an economic one. As numerous studies have shown, the value of a college degree in economic terms is unparalleled, even after the often-exorbitant cost is factored in. And given the Jewish community’s enormous investment in higher education—in the form of Jewish Studies, Israel Studies, and Holocaust Studies programs, not to mention Hillels and Chabads—the impulse to leave the university is shortsighted. So, where do go from here?

Earlier this year, Maimonides Fund president, Mark Charendoff, argued that American Jewish philanthropists should “identify a collegiate minyan, 10 small or midsized colleges with decent reputations but challenging financial prospects, and offer them a deal. In exchange for transformative financial gifts, these schools would show tangibly that they are willing to become welcoming centers for thriving Jewish life.”[5] These campuses would have strong curricular and co-curricular Jewish presences and they would embrace what Charendoff himself admits is an agenda identified with the American political right: anti-DEI, excellence over equity. It’s a bold proposal, and if Charendoff can be successful at it, it would represent an historic shift in both Jewish philanthropy and American Jewish higher education.

But this vision, like our broader Jewish communal discussion about higher education today, seems focused primarily on questions about the safety of Jewish students on campus and, to a lesser extent, on students’ internal capacities for navigating the lines between safety and discomfort. Those are important conversations. The immediate questions of safety, as well as the larger questions about social media and its fire-catalyzing effects, demand urgent attention. Yet if we want to understand contemporary university life on a deep level, we need to enter this larger conversation about the aims and purposes of these institutions, their visions of educated people and a healthy society. That conversation is not new, but it seems new to the Jewish world. In order to enter it, we should do what we do best: read texts and discuss them. We should read books like Veysey’s and Kimball’s, and we should put historical and contemporary visions of higher education in dialogue with our own traditional and modern sources. The remainder of this essay represents my own brief, modest attempt to do that.

Educational theorist Parker Palmer defines truth as “an eternal conversation about things that matter, conducted with passion and discipline.”[6] Elaborating on that definition, Palmer, writing with physicist Arthur Zajonc, invokes Martin Buber in offering a vision for what that pursuit of truth might look like in a renewed American university:

We have all had the experience of a conversation shifting and becoming a deep, free exchange of thoughts and feelings that seems to reach into and beyond the individual participants. Something new emerges, a transcendent communal whole that is greater than the sum of its parts. In such conversations we are caught up for a time in what some call ‘the social field’ generated by the quality of ‘presence’ necessary for true dialogue or community.”

Such conversations, they write, “allow us to explore shared concerns selflessly and achieve unexpected insights as our desire to ‘win’ as individuals yields to the desire that the full resources of the community be tapped for the common good.[7]

This educational vision may sound more like something we might recognize in informal or co-curricular settings like retreats, camps or educational trips than in a classroom. Yet Palmer and Zajonc invite us to steer higher education away from its deformative dangers and towards its positive potential using exactly this model: developing knowers with ways of knowing that recognize interdependence, community, and disciplined reflection on personal experience. These ways of knowing reflect what our own science is demonstrating over and over, namely that, far from being atomized beings, we—all of us who inhabit the cosmos—are in fact profoundly interconnected. And the suggestion at the heart of their book is that this is what higher education can and should look like: not simply a professional credential, not a pursuit of truth that is fundamentally accountable to no one, but an initiation into a community of learning, a society of mutual responsibility.

I believe this vision resonates with a profoundly Jewish sensibility about learning. Lee Shulman, professor emeritus of education at Stanford and former president of the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching, describes this sensibility well:

From the very first encounter with a text… the reader is compelled to interrogate the text, to recognize immediately its nuances and complexities. The reader is immediately drawn into the process of interpretation and the negotiation of meaning. I would argue, though not without opposition, that in proceeding this way, the Jewish tradition replaces the quest for certainty with a celebration of possibility.[8]

This description may sound familiar. It is central to the educational vision of a beit midrash and to the very design of a page of Talmud.

Shulman goes on to note that this Jewish sensibility centers a conception “of the ever-disputed nature and status of knowledge,” a vitally important notion in a time when our ideas about and experience of truth and knowledge are being pressured, tested, and contested as never before. Even as the boundaries of knowledge expand rapidly, the technological, media, and political worlds in which all of us, including college students, live are undergoing rapid, disorienting, and often dangerous changes. Yet rather than leading to the despair of living in a world unmoored from certainties, Shulman argues that a Jewishly inspired educational vision that develops students in dialectic and discussion rather than filling them with truth claims is precisely what we need. “Its paradigmatic embodiment is that of a ‘chevruta’ of two or more students studying or arguing together, rather than a rapt congregation listening devoutly to a teacher purveying unambiguous truths,” he writes. In an era when we fear for the future of our democracy, when we worry about the capacity of our most educated citizens to remain in relationship amid complexity and demagoguery, this Jewish educational vision can be of enormous value not only to Jews, but to society as a whole.

Shulman, Palmer, Zajonc, and Patel were leaders in a movement known as integrative education, which was once supported by funders including the Fetzer Institute and organizations like the American Association of Colleges and Universities. It had something of an Obama-era tone to it: simultaneously idealistic and pragmatist, a communitarian vision of the college campus. Like so many other middle-ground visions of the early years of the twenty-first century, this one has been pulled in opposite directions: towards more left-leaning visions animated, in part, by a politics of the marginalized and oppressed; and, as a backlash to those visions, towards more conservative views that push back on perceived wokeness. While both the AAC&U and Patel’s organization, Interfaith America, continue their work on college campuses, this vision of universities as sites of opportunity for dialogue across difference feels more attenuated, even pollyannaish, than it did ten or fifteen years ago.

Yet I would suggest that the essence of this centrist approach is one we as American Jews can and should reclaim—not only because it supports the well-being of Jewish students, but because it supports all students and the civic health of society. For decades, we have sought to support the immune systems of Jewish students so they could ward off the “pneumonia” Greenberg so feared. But the events of recent months demonstrate that this isn’t enough. We have to treat the underlying cold itself.

Rather than condemn or flee the campus, we should nurse it back to health. We should insist on holding together both appreciative and critical inquiry. We should invest in and support approaches to higher education that model and empower students to enter an eternal conversation about things that matter—including debates about what matters—with both passion and discipline. We should advocate visions of higher education in which all students are guided to engage their own stories as part of, rather than in some kind of opposition to, their larger formation as young people. We should support universities in centering ways of knowing and being that nurture the integration of mind, body, heart, and spirit. We should champion an education in which students become part of civic conversations across lines of difference, where the goal is not persuasion but listening and accompaniment, in addition to the development of the capacities for self-knowledge and resilience that such conversations require. We should do all these things because democratic life depends on it and, as the events on campuses across the country this past year have shown, so does the future of American Jewry.

There is, of course, much more to say, and I trust that responses to this article will bring up issues like college affordability and its relationship with the increasingly prohibitive economics of American Jewish life, not to mention discussions of alternative models. I welcome all of that—because I think a conversation about higher education in American Jewish life is long overdue. More than lighting Shabbat candles, celebrating Passover, or attending services on Yom Kippur, the single experience that American Jews share more than any other is sending our kids to college. I believe this moment of anxiety can also be one of possibility—if we are willing to step into rather than away from our colleges and universities.

Endnotes

[1] Alfred Jospe, “Jewish College Students in the United States,” The American Jewish Year Book 65 (1964), 131–45.

[2] Irving Greenberg, “Jewish Survival and the College Campus,” Judaism 17:3 (Summer 1968), 259–82.

[3] See the Yale Report of 1828.

[4] Bruce A. Kimball, Orators and Philosophers: A History of the Idea of Liberal Education (New York: Columbia University Teachers College Press, 1986).

[5] Mark Charendoff, “Goodbye, Columbia,” eJewishPhilanthropy, January 8, 2024.

[6] Parker J. Palmer, The Courage to Teach: Exploring the Inner Landscape of a Teacher’s Life (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1998), 130.

[7] Parker J. Palmer and Arthur Zajonc, The Heart of Higher Education: A Call for Renewal (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2010), 12.

[8] Lee S. Shulman, “Professing Understanding and Professing Faith: The Midrashic Imperative,” in The American University in a Post-Secular Age, Douglas Jacobsen & Rhonda Jacobsen, eds. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008).